The National Gallery of Art in Washington has just celebrated the reopening of its renovated and considerably expanded East Building designed by I. M. Pei. Refurbished and newly created galleries, plus a new roof terrace, exhibit an entirely new hang of the national collection of modern art, and three temporary shows.

The East Building of the National Gallery of Art, designed by I. M. Pei. Photo © Dennis Brack/Black Star. National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gallery Archives

‘The Gallery’, as it is known locally, was conceived by Andrew W. Mellon who took inspiration from his visits to London’s National Gallery. It opened in 1941 with Mellon’s foundation gift (which had already inspired others) in the Mellon-funded John Russell Pope building, offering free entry to all – Mellon had this enshrined in the museum’s charter. I. M. Pei’s large East Building extension opened in 1978; Laurie D. Olin’s sculpture garden was added in 1999. Now, on the gallery’s 75th anniversary, Perry Y. Chin – an associate of I. M. Pei’s New York office – has spruced up the old spaces and made dramatic, light-filled additions. A programme of birthday events includes a weekend-long public party on 5–6 November and, at long last, some evening openings scheduled over six months.

Installation view of works from the NGA’s collection of Mark Rothko, on view in the East Building, Tower 1 galleries. Photo: Rob Shelley © 2016 Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art, Washington

Two tower galleries showcase permanent collection pieces by Alexander Calder and Mark Rothko, while a third is filled with a temporary display of 15 strident profile works by Barbara Kruger (b. 1945). A second temporary show is the major gift of 33 contemporary photographs promised to the gallery by Robert E. Meyerhoff and Rheda Becker, among them works by Thomas Demand, Thomas Struth and Hiroshi Sugimoto – photography is an area the gallery is keenly expanding. Up on the roof terrace, Katharina Fritsch’s vibrant blue Hahn/Cock (2013) perches on the edge looking outwards, a reminder that there is also an entirely new arrival to explore on the museum-filled National Mall – the National Museum of African American History and Culture, whose massive upside-down ziggurat building is designed by British architect David Adjaye.

The new roof terrace of the National Gallery of Art East Building. Several sculptures are on view, including Hahn/Cock (2013) by Katharina Fritsch, on long-term loan from Glenstone Museum, Potomac, Maryland. © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn. Photo: Rob Shelley © 2016 Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art, Washington

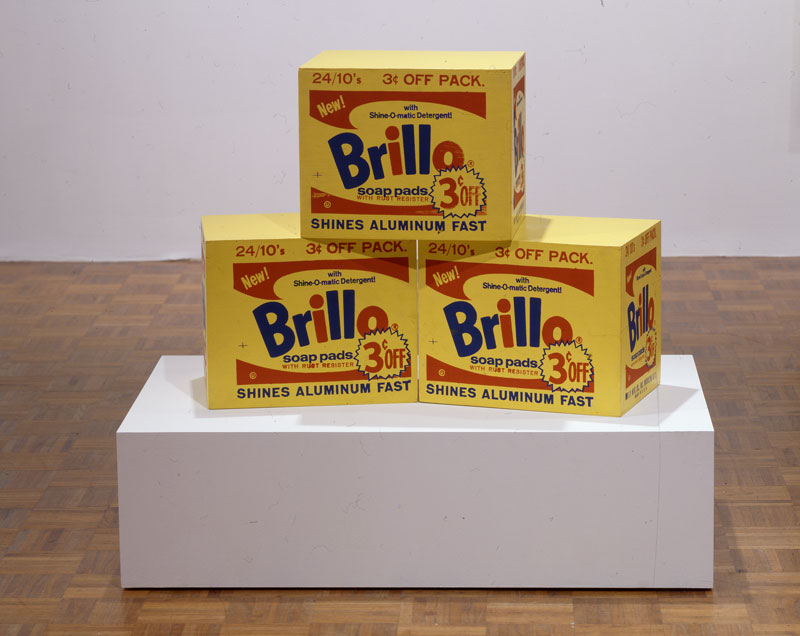

It is the third temporary show that is especially exciting: a suite of large galleries filled with works promised to the NGA by the remarkable Virginia Dwan. Born in 1931 and heiress to the Minnesota-based conglomerate 3M, she has used her financial privilege, insight and phenomenal energy to be a loyal patron and dealer to artists whose daring in pop, conceptual, minimal and land art was hard at first for most people to recognise. She ran Dwan Gallery in LA (1959–67) and New York (1965–71) where she staged 134 shows. She founded the Dwan Light Sanctuary in New Mexico (opened 1996). She bravely gave Robert Rauschenberg a solo show in LA (where not one piece sold). She staged the landmark shows ‘My Country ‘Tis of Thee’ in 1962 and ‘Boxes’ in 1964 (where Warhol first showed his Brillo boxes), and much more. Currently, MIT is making a comprehensive catalogue of the works she handled, while Dwan herself is working on a book of military cemetery photography.

Brillo Box (c. 1964), Andy Warhol © 2016 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Jerry L. Thompson

Now, shortly before her 85th birthday, 100 or so pieces of the 250 comprising Virginia Dwan’s promised gift to the gallery have gone on show, complemented by loans that enrich their context. The display includes works made from the 1950s to the end of the ’70s by 52 modern masters such as Carl Andre, Arman, Dan Flavin, Yves Klein, Agnes Martin, Jean Tinguely and many by Sol LeWitt. Two show-stoppers are Robert Rauschenberg’s Coexistence (1962) and Robert Smithson’s Gyrostasis of 1967, a smaller iteration of his better-known piece on view at the Hirshhorn Museum nearby. However, much of her gift has rarely been seen and, indeed, arrives straight off her New York apartment walls.

Gyrostasis (1967), Robert Smithson. © Holt-Smithson Foundation/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

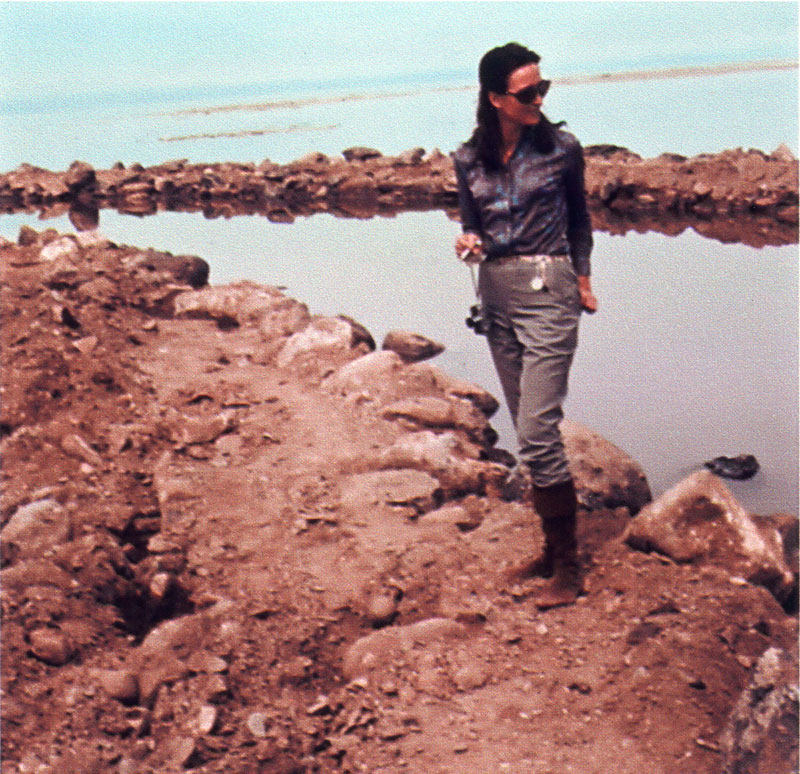

As expected, the curator of the show James Meyer, formerly at the NGA and now deputy director and chief curator of the Dia Art Foundation, is over the moon. ‘It is the impeccable quality! She had a marvelous eye, always chose the best.’ He speaks fast, brimful of excitement, moments before 450 people arrive for the opening. ‘The provenance is perfect, always direct from the artist or from the gallery representing the artist. She had direct relations with the artists, she gave them stipends, she made all the difference for them.’ He wants to emphasise this point. ‘She made their work possible. Art was changing so much it needed a new kind of philanthropy in the ’60s. She was adaptable to new technology, sites and materials.’ Meyer does not stop: ‘She made works possible by underwriting them, by buying land for them. She supported young artists both financially and morally.’ He cites Michael Heizer’s Double Negative (1970), a piece of land art in Nevada State’s Moapa Valley. Dwan bought the 60-acre site for it, and later donated the piece to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA); the NGA’s show includes huge photo murals of Dwan’s land art patronage.

Virginia Dwan at Spiral Jetty (c. 1971; #35 in Chronology), Nancy Holt. Courtesy Holt Archives

This week, the National Museum of African American History and Culture is enjoying the spotlight, leaving the National Gallery and its stunning historical and expanded modern collections undeservedly in the shadows – for the moment. Time will redress that.

‘Los Angeles to New York: Dwan Gallery, 1959–1971’ is at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, until 29 January 2017, and will travel to Los Angeles County Museum of Art from 19 March–10 September 2017.