In Stephen King’s novel The Shining (1977), Jack Torrance, a troubled writer who is looking after the out-of-season Overlook Hotel with his young family, discovers and poisons a wasps’ nest. His son Danny is fascinated by the grey, brain-like paper structure and places it in his bedroom, to the dismay of Jack’s wife, Wendy.

‘She didn’t like the idea of that thing, constructed from the chewings and saliva of so many alien creatures, lying within a foot of her sleeping son’s head,’ King writes. Wendy is promptly vindicated when the nest proves not so dead after all and vengeful wasps emerge. A drastic oversight by Jack, whose duty of care towards his family is being fatally eroded by alcoholism – or a microcosm of the hotel itself, swarming with malevolent entities that should be dead?

King didn’t have to change the popular perception of the wasp much to fit it into the horror genre. They’re seen as spiteful, dangerous and persistent creatures, and as the scourge of summer – ‘nature’s stripy bastards’ in the words of Viz magazine. ‘World of Wasps’, an exhibition now at the Grant Museum of Zoology in London, aims to swat some of these preconceptions, repositioning the beer-garden menace as an evolutionary marvel, a misunderstood ally, an ecological boon, largely harmless if left to its own devices and – last but not least – a genius at building.

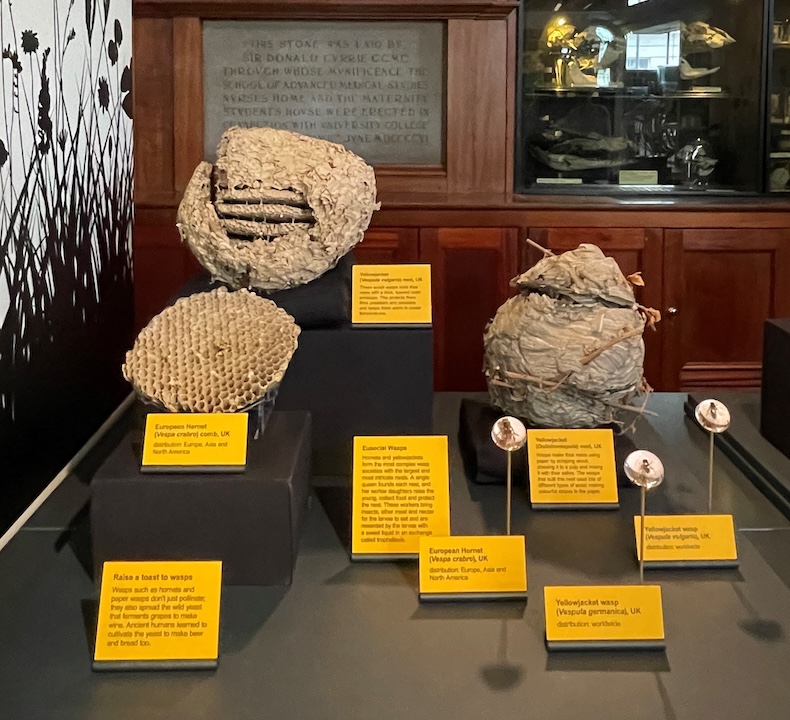

Danny Torrance wasn’t wrong to be fascinated by the wasp’s nest, and they take centre stage at ‘World of Wasps’, which was overseen by Dr Seirian Sumner’s lab at UCL’s Centre for Biodiversity and Environment Research. An installation made by the designer and paper sculptor Peter Ayres – who happens to be my cousin – shows the inner and outer structure of the typical nest: a squamous shell on the outside, and horizontal ‘galleries’ of hexagonal combs within. Visitors can explore a nest from within, using virtual reality. But being the Grant Museum – an unbelievable hoard of zoological specimens – there is also a remarkable display of real (untenanted) nests, from the impossibly tiny clay orb of the potter wasp to the beachball-size megastructure of the yellowjacket, clad in thick shaggy armour.

The ingenuity and diversity of these structures is breathtaking. But the sense of disgust also lingers, and it may be worth lingering with it, as disgust is one of the more interesting possible reactions to works of creation, provided you resist the impulse to turn away. The industry on display is undeniable, so why is it hard to love? Most wasp species are parasitic – the oak wasp has the astounding ability to genetically alter trees to grow a home for it – and parasitism is inherently unnerving. But as Insect Architecture: How Insects Build, Engineer, and Shape Their World by Tom Jackson and Michael S. Engel (Princeton University Press, coming in September 2025) reveals, nest-building is an evolutionary step beyond parasitism: rather than raising their young in a plant or animal (as many wasps still do), the nest-builders have taken matters into their own hands. But the new-builds can be as disturbing as the squatting arrangements. All that chewing and saliva, as Wendy said, and the obscurely horrid grey impasto layering of some of the paper nests, especially the larger ones. The smaller nests, which can be bead-like in their smoothness and evenness, are automatically less unsettling. It’s the uncontained, promiscuous nature of the larger, sprawling structures that gives them some of their perverse appeal. Deep down there’s the suspicion that they might just keep spreading if not decisively checked.

In the wild, this can lead to the absorption of human structures and objects, sometimes with very creepy consequences. Paul Dobraszczyk’s recent book Animal Architecture: Beasts, Buildings and Us (2023) includes a photo of a wasp’s nest that has grown under a hanging wooden head, a true nightmare – but truly compelling. Dobraszczyk suggests that some of the unease caused by wasp nests – and similar insect-built structures – is that they are undoubtedly the product of intelligence, but that intelligence is undoubtedly different to ours, emerging not consciously from individuality but intuitively from ‘ceaseless flows of communication between bodies, buildings and environments that nevertheless sometimes produce extraordinary works of architecture’.

This swarm approach to design is providing inspiration to some humans, as Dobraszczyk explores, suggesting ‘the possibility of an architecture that does not arise from blueprints and hierarchical forms of control, but rather emerges from local conditions’. It seems probable that more of the human world will inevitably be designed according to faintly inhuman techniques – not the insubstantial and derivative fantasies of ‘generative AI’ but through the deeper application of computing power to the essentials of problem-solving that design and construction entail. What’s interesting is that Dobraszczyk’s leading example – developed by the animal researcher Guy Theraulaz – used the decision-making exhibited by wasps in expanding their nests to create a procedural tool for architecture that generated multiple designs from set inputs. In other words, the deliberations of the hive mind led to increased diversity, rather than uniformity.

This brings to mind the architect Peter Eisenman’s experiments in the 1980s with the imperfect cloning of modular structures according to ‘genetic’ rules, such as in his design of the Carnegie Mellon Research Institute in Pittsburgh. Which doesn’t necessarily lead us away from unease: after all, I first encountered that work in Joshua Comaroff and Ong Ker-Shing’s excellent book Horror in Architecture (2013, and republished last year in an expanded, ‘re-animated’ edition by the University of Minnesota Press). So perhaps a degree of horror is inevitable in wasp architecture, but fortunately we can go down to the Grant Museum to get over it.

‘World of Wasps’ is at the Grant Museum of Zoology, London, until 24 January 2026.