From the December 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

In 1961, out of the blue, Wayne Thiebaud developed a sweet tooth. Two years earlier, he had finished a canvas called Meat Counter (1956–59), the second painting in this show of his work at the Courtauld. Its subject was much as its title suggests – four rolled joints of what is perhaps beef on top of a vitrine holding cuts of a smaller size. In 1962, Thiebaud made what may be seen as a pendant to this work – a larger painting, roughly twice the size of the first, called Candy Counter. The die was cast.

Much remained the same. Counters, whether in butchers or sweet shops, are about display, and display is about consumption. In the case of these two pictures, that consumption has a double meaning.

As with a growing number of American artists in the early 1960s, Thiebaud’s fascination was with what the social critic Vance Packard had recently popularised (or unpopularised) as consumerism. Where Pop artists would tend to focus on consumer durables, though – Chevrolets, white goods, and so on – Thiebaud’s fascination was with things that would be literally consumed. Above all, his eye was caught by cakes.

You can see why these might have appealed. Both Meat Counter and Candy Counter were underpinned by an interest in synaesthesia; that is to say, with producing a visual image that would evoke other senses as well. The palette and brushwork of Meat Counter are meaty, carnal. You can imagine Francis Bacon looking at the painting and sniffing. But in Candy Counter, the loop is closed. Thiebaud’s brushwork becomes that of a confectioner, so that the picture both represents confectionery and is itself a confection.

This tendency reached its apogee in works such as Cakes (1963), on loan from the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. Here, Thiebaud’s paint is laid on the canvas like icing. Were you to lick it, you imagine, it would taste of the thing it depicts. If that seems an easy enough trick, though, Cakes and its coevals are more complex than they seem.

Between Meat Counter and Candy Counter, there was a change of gender. Butchery, in 1961, was men’s work, just as red meat was men’s food. Cakes were baked by women and, proverbially at least, eaten by them, being made of sugar and spice and all things nice. The fictional baker Betty Crocker – created for advertising purposes in 1921, the year after Thiebaud’s birth – was familiar to a whole generation.

A decade before John Berger, the painter of Cakes had changed his gaze from a male to a female one. He was not just taking as his subject objects thought of as womanly, but producing them in a womanly way. This lent works such as Display Cakes (1963) a curious unease. For all its vitreous perfection, there is something uncanny about these patisserie paintings. There is also more going on in them intellectually than their sugared surfaces suggest.

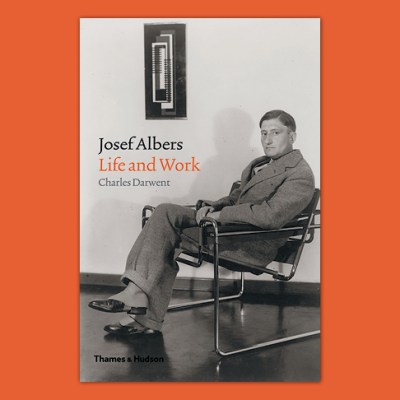

Let me digress. To celebrate the publication of my biography of Josef Albers in 2018, a friend made me a tray of Albers cupcakes. Her intention was playful. What could be less suited to icing than the soft-hard-edged remorselessness of Albers’s celebrated series Homage to the Square?

Unexpectedly, the joke backfired. The Homages worked rather well in sugar: the cupcakes not only tasted nice, they looked nice, too. The assumption that geometry and lusciousness were antithetical to each other was wrong. Albers himself had known this. ‘[My paints] come out of the tube and I smear them on like butter on my pumpernickel,’ he said. As with butter, so with icing. Bound up in the idea of baking as women’s work was an assumption of its triviality.

It may be useful to approach Thiebaud via Albers rather than, say, Andy Warhol. One of the non-edible subjects in the show is Four Pinball Machines (1962). The screens of these are a painterly in-joke: one shows the modernist grid, another a Jasper Johns target – the first of these had appeared in 1955 – and a third what looks very like an Albers Homage. It is clear, too, that Thiebaud’s post-1961 sweet tooth also had geometric underpinnings. If Albers had laid claim to the square, works such as Pie Rows (1961) and Boston Cremes (1962) are studies in triangles and parallelograms, Cakes and Display Cakes in circles.

There are other Albers parallels, too. Thiebaud had turned his back on meat as a subject in part because he found it insufficiently processed. ‘I paint those foods that have mostly undergone some kind of change or metamorphosis,’ he said. His paintings of cakes took the process of process a step further, from butter and sugar to iced sponge, from iced sponge to paint.

Bound up in all this was an idea of the American Dream, built on mass production, a faith in standardisation – that any car that rolled off an assembly line would be identical to the cars before and after it, and that this likeness was desirable. Albers’ Homages, too, seemed to roll out of the painter’s Connecticut basement. Nearly 3,000 of them survive, each based on one of four templates. And yet these paintings are Romantic rather than classical, being at heart concerned with the impossibility of sameness. The apparently hard edges of Albers’ squares are soft as butter, hand-drawn rather than ruled. So, too, with the triangles of Thiebaud’s Pies.

The drive of 20th-century American painting, as of American manufacturing, had been towards working in series, yet Thiebaud’s triangular slices of cake and pie, like Albers’ squared pumpernickel, showed that standardisation was a dream; also, perhaps, a nightmare. The work in the Courtauld is above all a celebration of the imprecise hand over the immaculate eye.

‘Wayne Thiebaud: American Still Life’ is at the Courtauld Gallery, London, until 18 January 2026.

From the December 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.