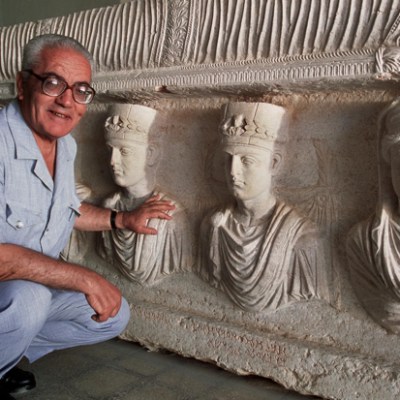

On a flying visit to London on Thursday, Syria’s director-general of antiquities and museums, Maamoun Abdulkarim, made a direct plea to the international community: to take action to protect our ‘shared heritage’ in the Middle East, before it is too late.

Abdulkarim was speaking at the first of a series of heritage talks organised by the World Monuments Fund. His first-hand account of the dire situation in Syria looked well beyond Palmyra – the UNESCO world heritage site whose deliberate destruction at the hands of ISIS has been a focus of global media attention. But alongside his discussion of the country’s many cultural losses (‘every day I receive bad news’) he also highlighted his department’s ongoing and impressive efforts to safeguard Syria’s remaining treasures.

Syrian officials in the Directorate-General of Antiquities and Museums (DGAM), which employs around 2,500 people and is based in Damascus, were well aware of the danger to the country’s cultural property when hostilities first broke out – the looting of Iraq’s National Museum in 2003 was fresh in everyone’s minds. They closed Syria’s museums and moved some 300,000 objects (the vast majority of national collection items) to safe locations, where most of them still reside.

Buildings, towns and archaeological sites fared less well. Abdulkarim compared the war damage in Aleppo to that sustained by some European cities in the Second World War: some 150 historic buildings, 1000 souks, and hundreds of homes have been affected. But while scenes of devastation have reached international news channels, local restoration efforts, which are already underway across the country, have received little press. Deserted and fire-damaged buildings are repaired as soon as possible – ‘if this building were to stay like this through the winters, there would be a lot of damage,’ he explained of one example, a church whose roof had collapsed. Displaced residents have been encouraged to shelter in historic buildings, rather than carry off building materials for their own use. For the heritage officials and volunteers who have stayed put in Syria, the protection and recovery of cultural heritage are one and the same: only through emergency repairs can the prospect of more long-term restoration be kept alive.

Outside of immediate conflict zones a second big problem for Abdulkarim’s department is theft. He explained that, while there had always been looting at Syrian archaeological sites, it used to happen on a relatively small scale, ‘at night, in small groups’. Abdulkarim blamed foreign mafias for organising the more extensive recent plunder, using hundreds of local recruits and heavy machinery such as bulldozers to start a lucrative new criminal industry.

Collateral war damage and opportunistic theft were known risks of protracted conflict – although the extent and organisation of the latter has been a surprise. But there is very little precedent for the actions of ISIS, whose particular brand of cultural violence Abdulkarim assigns to its own category – a ‘destruction of vengeance’. He pointed out that the group’s ‘ideological’ iconoclasm extended to mausoleums, mosques, churches and portable antiquities (ISIS also plays a key role in the looting networks) but dwelt on their attacks in Palmyra, Syria’s most prized historic site. Abdulkarim’s departmental photographs of the destroyed temples of Baalshamin and Bel (along with the less familiar Tower Tombs and other sites) lent a depressing immediacy to news that has already been widely publicised in the UK.

The Temple of Bel, Palmyra, before its destruction by ISIS © Directorate-General for Antiquities and Museums, Syria

ISIS have laid waste to the area’s many monuments in a calculated manner designed to hold the world’s attention, and to maximise the demoralising effect on the local community. But it was the murder of Khaled al-Asaad, the 83-year-old Palmyrene archaeologist, that sent the most chilling and distressing message to the world. Abdulkarim spoke warmly of his personal friend, a ‘gentleman, a modest man’ who refused Abdulkarim’s entreaty to leave the town. His subsequent murder was a ‘message of terror’ that deliberately robbed the community of one of its most respected elders. That ISIS militants first interrogated al-Asaad about the whereabouts of a rumoured two tonnes of buried gold proved them to be ‘ignorant people’, whose motivations are criminal rather than ideological, Abdulkarim argued. In the face of all this, Abdulkarim’s aspirations for Palmyra and commitment to its recovery were apparent: ‘It is my hope that, one day, I will rebuild this,’ he declared at one stage, looking at a picture of the rubble of the Temple of Baalshamin.

The Temple of Baalshamin, Palmyra, before its destruction by ISIS © Directorate-General for Antiquities and Museums, Syria

ISIS’s cold-blooded attacks on heritage have, understandably, been the focus of media attention this year, and they were the only named group to be discussed by Abdulkarim. What wasn’t discussed was how the actions of Bashar al-Assad’s regime have affected the cultural fabric of the country. Abdulkarim’s reticence was to be expected – he works for the government (but has refused to take a salary) – but the lack of an open question session at the end of the talk meant a major topic was left alone.

Throughout his address, Abdulkarim instead reiterated the importance of widespread cooperation to end cultural destruction – irrespective of politics, religion or geography. His department relies on the assistance of local communities, to which he has appealed for help to prevent looting and damage, but it also counts on the international community to stem wider trafficking of cultural artefacts at national borders and on the global market. As Abdulkarim made clear, ‘The dangers surrounding the Syrian archaeological heritage are growing beyond our capabilities.’

Abdulkarim was in Paris on Friday evening for a UNESCO annual meeting when ISIS terrorists launched a series of attacks on the city. Faced with such horrific violence and loss of life, it is easy to forget about the concerns that Syria’s antiquities chief had travelled so far to highlight. But in the long term, they cannot be separated. ‘It’s culture, not politics,’ Abdulkarim explained to his London audience. ‘We have one heritage. Common knowledge, common identity, common responsibility.’

Maamoun Abdulkarim’s talk in London on Thursday 12 November was organised by the World Monuments Fund and hosted by the Royal Geographical Society.

This article has been amended: Abdulkarim was in Paris on Friday 13 November for a UNESCO annual meeting, not to give a talk as originally stated.