Focusing on her collage and photomontage works, the Whitechapel Gallery’s Hannah Höch exhibition is her third major survey, and the first to be held in the UK. Her work was deeply critical of patriarchal power, satirising both the dominant political regimes and the Dadaist circles in which she moved. Her post-war work took on a more formal agenda, celebrating the enjoyment and craft of making.

Hannah Höch trained at the School of Applied Arts in Berlin, and went on to have a successful career as a pattern designer for a major publisher of women’s magazines. She was greatly influenced by this early experience, as is evident in her virtuoso compositions, and her funny (yet also deadly serious) appropriation of media imagery, particularly images of women. She never regarded her craft as separate from her art practice, and eloquently argued her case in a manifesto published in Embroidery and Lace in 1918:

Embroidery is very closely related to painting. It is constantly changing with every new style each epoch brings. It is an art and ought to be treated like one… you, craftswomen, modern women, who feel that your spirit is in your work, who are determined to lay claim to your rights (economic and moral), who believe your feet are firmly planted in reality, at least Y-O-U should know that your embroidery work is a documentation of your own era.

Höch called upon women to take their craft seriously, despite it not receiving the institutional and critical recognition it deserved in a male-dominated art world.

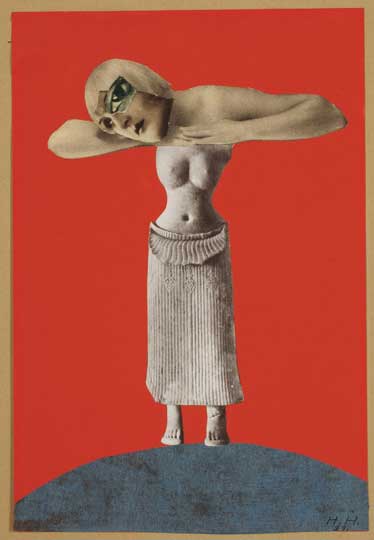

Her Dada works, such as her early political collages and the series From an Ethnographic Museum, use photomontage – a technique that Höch pioneered – to reveal the construction of racial and gender stereotypes through media imagery. Figures are assembled and layered from incoherent parts, unsettling the idea of a unitary body or a singular, coherent identity.

Untitled (From an Ethnographic Museum) (1930),

Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe, Hamburg. Photo: Maria Thrun

Read the curator’s introduction to Hannah Höch

During the Nazi years Höch moved to a small house outside Berlin. She was not permitted to make or exhibit art, because of the political repression of ‘degenerate art’ and her association with the Dadaists. Instead she produced a number of scrapbooks, in which she pasted photographs from magazines and newspapers. These images are juxtaposed and grouped rather than collaged, constituting a vast atlas of imagery akin to Aby Warburg’s Mnemosyne Atlas; an attempt to collate a taxonomy of imagery through parataxis.

The entire first floor gallery is given over to her collage works from the post-war period. Decidedly more abstract than her early works – which often depicted well-known figures, and had explicitly satirical themes – these works reveal a return to her early pattern work, a reconnection with textiles through collage, and could certainly be seen as a kind of ‘embroidery’. At the same time, titles such as Raumfahrt (Space Travel) hint at her ongoing fascination with the manipulation of popular imagination by the media.

The largest collage on display, right at the end of the exhibition, is Lebensbild (Life Portrait), in which Höch charts her own shifting identity, collaging together pictures of herself at various ages, her cactii, her pets, and her lovers, as well as photographic reproductions of earlier artworks. A moving chronicle of a long and successful life and career, Lebensbild is the perfect ending to a display that hopefully marks the beginning of whole new generation’s interest in Hannah Höch’s pertinent and impertinent work.

‘Hannah Höch’ is at the Whitechapel Gallery, London, until 23 March.