It’s the morning after the night before on Wembley Way, and the shattered glass and discarded cans have mostly been bagged up or swept to the side of the road. A couple of large men, one with a tattoo of three lions on his calf, bowl down the street looking lost. Football isn’t coming home after all.

Wembley Park, redeveloped around the new Wembley Stadium over the past 20 years or so, remains a place in search of an identity – which is something that can’t be achieved merely by the presence of international football. As with the Olympics-centred development of Stratford in East London, there’s a sense in which the space has been constructed to engineer the community and locale desired by its planners and developers, rather than to enhance the environment of those who lived in the area already. That means apartment blocks and branded retail alongside plenty of ‘pocket parks’, ‘tree-lined boulevards’, and even a ‘leafy, tranquil green haven’ – as developers Quintain put it.

Reasonable enough, you might think – build it and they will come is not the worst mantra, and there’s plenty to be said for a ‘designer outlet’ and glass-fronted coffee shops, even if they don’t compensate for living with the violence and anti-social behaviour seen in the lead up to the final of the Euros. It does mean, however, that projects such as the Wembley Art Trail – 14 public artworks dotted around between the station and the stadium – face something of an uphill battle.

Take Power in Unity, Micah Purnell’s new installation which sees Wembley’s famous ‘Spanish Steps’ covered brightly in the slogan, drawing the eye up the three words to reach the stadium itself. It’s striking, even visually dramatic, but it fits so well in its surrounds as to be nearly indistinguishable as a piece of art; it’s almost surprising that the developers hadn’t already done it.

Staircase wit? Micah Purnell’s Power in Unity installed on the ‘Spanish Steps’ at Wembley Park, London. Photo: Chris Winter/Wembley Park

Far more interesting is another new installation by London design studio HagenHinderdael (four works have been added to the trail for this summer). Meadows of Change comprises three red K2 phone boxes in a row, each containing growing meadow plants, backlit by an arc of lights that echoes the arch of Wembley Stadium. At night, the boxes are spotlit on either side to represent the Twin Towers of the old Empire Stadium.

Meadows of Change (2021), HagenHinderdael

It’s a powerful piece because it engages with the history of the place (which was once Wembley Green, and then the site of the old stadium), but also asks questions about the present. The K2 was designed in 1924 by Giles Gilbert Scott, the year of the British Empire Exhibition at Wembley Park and a year after the original stadium opened. The phone boxes here become literal touchstones, for an idea of Great Britain, and for continuity, even as the meadow plants inside threaten to outgrow them.

The best works on the trail all engage with the history of place or the meaning of urban experience. Mr Doodle’s graffiti-covered cinder blocks in Market Square provide a cheeky and amusing take on some memorable Wembley moments, but more interestingly they also recall the kind of anti-terrorist prevention measures we have become used to throughout the city, especially near large tourist centres.

Similarly, Jason Bruges’ Shadow Wall, in which the walls of an underpass light up as you walk past, is both fun but also somehow true – you see your shadow in light next to you as you might notice other fans on your way to a game, peripherally. It takes on not just the space, but also the dislocations and weirdness of sociability and shared experience at the present moment.

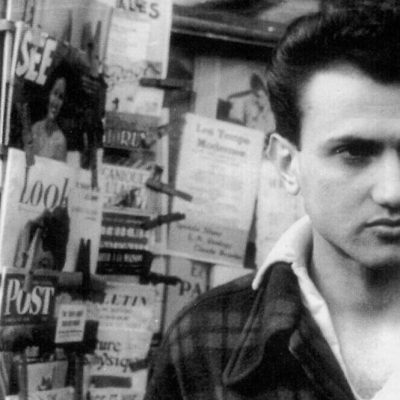

The other notable new art is a set of photographs by pseudonymous French photographer and street artist JR, as part of his Inside Out London project, which sees black and white photographs of Londoners appearing across the city and a travelling photobooth enabling people to have their own portraits taken.

Displayed here in a new, permanent outdoor gallery, the photos are a series of large, extremely close shots of eyes, sometimes reflecting light, other times reflecting a person (the photographer?) in them.

Inside Out London (2021), JR

The effect is compelling, accumulating into a kindly interrogation, as you look into them and they look back at you and whatever else it is they’re looking at. The imagined proximity is surprisingly comforting where it might be disconcerting. It as if what’s been really missed over the past 18 months of masks and distance is seeing the whites of each other’s eyes.

Further information about the Wembley Park Art Trail is available here.