Being Armenian in the premodern era held a multiplicity of meanings, despite the persistence of traditions that sought to present it as unchanging and singular. The latter included the belief that Armenians were descended from the eponymous figure of Hayk (despite the dubious etymological link, the classical Armenian term for ‘Armenian’ is Hay); that they comprised the first Christian nation after the healing and conversion of king Trdat by St Grigor the Illuminator in the early fourth century, and so before the conversion of Constantine and the Edict of Milan in 313 AD gave Christianity a legal status in the Roman Empire; that to be Armenian was to be Christian, acknowledging the headship of a Catholicos (the title used for the head of the Armenian Church) and recognising a confession of faith and forms of worship and liturgy written, spoken and sung in Armenian. The reality, however, is that Armenian identity was continually evolving, open to revision and reimagination. What it meant to be Armenian in the 7th century, therefore, was not the same as what it meant to be Armenian in the 10th century or the 17th century, just as what it meant to be Armenian at any one moment in time will have differed from district to district and from community to community. The different expressions of Armenian-ness that emerged, coexisted and vanished over the centuries bear witness to the complex and often turbulent historical experience of Armenians, as they engaged with and responded to intrusive hegemonic powers, regional authorities and local rivals, and reflect the movements of communities and the development of commercial networks down to the present day.

The Church of the Holy Cross, built 915–921, on Aght‘amar Island, Lake Van, Turkey (photo: 2004). Photo: ImageBROKER/Alamy Stock Photos

There is no simple answer to the question of where Armenia was situated because, once again, its definition is contingent on date, context and perspective. Adopting a political definition is not as helpful as it might seem. Although distinct kingdoms of Armenia existed at various times – first under the Arsacid dynasty, down to 428, then under members of the Bagratuni house, between 884 and 1064, and finally under Rupenid and then Hetumid rule between 1198/99 and 1375 – they did not extend across the same spaces. Indeed, from a territorial perspective, the kingdom of Cilician Armenia (in south-eastern Turkey) did not overlap at all with the kingdoms of Greater Armenia which preceded it. These were situated further east, extending across territories situated today in eastern Turkey, northern Syria and north-western Iran as well as the Republic itself. Moreover, these kingdoms were not the inevitable outcomes of some mysterious process of independent state formation. The Arsacids were closely related to the Parthian kings of Persia and had been appointed by them. Ashot I Bagratuni was sent a crown from the ‘Abbasid caliph, al Mu‘tamid, while the first Rupenid king, Levon I, received a crown in the cathedral of Tarsus on 6 January 1198 (or 1199 – the date is still disputed) from the German emperor Henry VI. Nor were these Armenian kingdoms singular. At the end of the fourth century, there were two Arsacid kings, one for the Roman sector of Armenia, the other for the Persian sector. Within a generation of Ashot I Bagratuni’s coronation, the leading prince from a rival noble family, Gagik Artsruni, was crowned king in 908 with a crown sent from a local emir. This duality was recognised at the time, in a treatise referring to ‘the days of the two brave and noble-lineaged kings of Armenia, powerful and independent, the crowned-by-Christ lord Gagik Artsruni, king of Armenia, and the peace-loving and sweet-tempered lord Abas Bagratuni, powerful king of Greater Armenia’. And this is without considering how to treat regions designated as provinces of Armenia by Roman, Persian or ‘Abbasid authorities, or those communities of Armenians settled elsewhere, whether in Naples or Jerusalem, the Balkans or the Crimea. It is therefore perhaps more helpful to understand ‘Armenia’ in social and cultural terms, defining regions and settlements where those who identified as Armenian lived, rather than in political or territorial terms, although at times these also held meaning. This also holds true for the present day. The modern Republic of Armenia that extends across only a part of historic Armenia, with its population of 3 million matched by a similar total in the Armenian diaspora communities settled throughout the world.

Stela depicting a figure often identified as king Trdat (left) (4th/5th century), Kharabavank, Armenia. History Museum of Armenia, Yerevan.

The exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, ‘Armenia!’ (until 13 January 2019), celebrates both the richness and the diversity of Armenian artistic and cultural production and the identities which these express. It brings together an impressive collection of objects – manuscripts, textiles, khachkars (cross stones) and other carvings in stone and wood, liturgical vessels, ceramics and jewellery. These attest a predominantly – though by no means exclusively – Christian world, revealing that Armenian artistic traditions were tied to Christian belief, worship and display. Yet we should remember that the Christian character of Armenian art, as it is presented here, is the product of the particular circumstances of preservation. These manuscripts and objects were cherished in patriarchal treasuries, monastic libraries and individual churches. These had been present in the Armenian landscape for centuries and served as guardians of Armenian tradition. Much less evidence for Armenian secular or popular artistic tradition has survived, at least from the premodern period, although there are tantalising proofs of its existence. Anania of Shirak, an Armenian intellectual active in the middle of the 7th century, imagined a scenario for one of his mathematical problems in which a very large silver container was broken up and refashioned into plates and goblets of various different weights and dimensions. This implies an active metalworking tradition in Armenia in late antiquity although no objects of this provenance have been found or identified. Arabic geographical writers of the 10th century praised Armenian textile manufacture, including carpets and rugs – ‘without equal anywhere in the world’ according to Ibn Hawqal – but the earliest dated liturgical textile, an embroidered banner depicting St Grigor, dates to the middle of the 15th century. And in 1613, shortly after his death in New Julfa outside Isfahan, the Armenian artist Hakob was remembered as one who ‘decorated the Scriptures with many different colours, with gold and azure, who was a decorator of houses and who was a skilful scribe’. The Armenian merchants, khojas, forcibly transferred to New Julfa by Shah ‘Abbas I in 1604, commissioned richly illuminated manuscripts for themselves and their newly founded churches but this commemoration suggests that they also commissioned frescoes for their houses; again no trace of these painted interiors survives. Almost nothing of the Armenian royal or noble palaces or merchant houses has been unearthed; only the charred fragments of elaborate wooden carvings and plaster decoration discovered by Nicholas Marr during his excavation of the east hall in the citadel at Ani a century ago hint at the visual splendour of the Bagratuni court in the 10th and 11th centuries.

Bowl (mid 9th century), found at Dvin, Armenia. History Museum of Armenia, Yerevan.

What then can the study of Armenian art contribute to the complicated and contested questions of Armenian identity and tradition? Despite its mainly Christian character, closer inspection of what has come down to us reveals that Armenian artists both responded on an individual basis to the achievements of their predecessors and also interacted with neighbouring visual cultures, creating works which were simultaneously engaged with past traditions and present circumstances. Being an Armenian artist did not preclude participation in a cross-cultural artistic milieu, just as being Armenian did not preclude employment in and advancement through the service of a non-Armenian power. Vardan Mamikonean is known today as the valiant leader of the Armenians who fought to defend his people’s Christian traditions and who was martyred at the battle of Avarayr in 451. The first Armenian historian to record these events, Łazar P‘arpets‘i, comments that he was also remembered by Persians as ‘a man of courage, who assisted the lord of Eran (that is, the Persian king)’ and that ‘the memory of his greatest actions persists in the land of Eran’. Even Vardan therefore had fought for the Persians in the past. That element of the tradition was not retained in the retelling of the episode by a later Armenian historian, Yeghishe, who represented the conflict as a simple dichotomy, Christian Armenians against Zoroastrian Persians, thereby sharpening the differences between the two. Strikingly it was Yeghishe’s version which came to be preferred, to the extent that Łazar’s History, a crucial witness to Armenian experiences in pre-Islamic Persia, has been preserved in only a single late 17th-century manuscript, to all intents and purposes forgotten. If an understanding of the Armenian past is susceptible to change and refinement depending on the circumstances and context of construction, so we should expect the Armenian artistic tradition to be similarly complex. Just as medieval Armenian historical compositions told their own stories in their own ways and were not instalments in a single grand narrative, so Armenian artists cannot be fitted into a simple or singular tradition.

Studying what little survives of artistic and cultural production from the 10th-century kingdom of Vaspurakan shows how difficult it can be to define even a regional artistic tradition. On the one hand, the Gospels manuscript given by Queen Mlk‘e, wife of king Gagik Artsruni, to the church of the Holy Mother of God at Varag in 912 looks back to late antiquity. The headpieces above the Canon Tables of Eusebius assert an Alexandrian origin. Two depict fishermen standing on reed boats with crocodiles patrolling menacingly beneath them while two others display different types of fish caught or known, as well as what can only be an octopus. On the other hand, the inspiration for the much-studied decoration of the famous church of the Holy Cross on the island of Aght‘amar in Lake Van commissioned by Gagik and built between 915 and 921, is much harder to interpret. Its elaborate exterior sculptures, including three friezes containing animals, fruits and human figures as well as separate cycles depicting Old Testament narratives, Apostles and Armenian kings and saints, are unprecedented in Armenian tradition, although pre-Islamic Persian, Umayyad and ‘Abbasid structures, in stucco rather than stone, have been proposed. Cross-cultural interaction is also found in contemporary literature. In one historical composition, Gagik is represented visiting the Sajid emir of Azerbaijan, Yusuf, and discussing practical, theoretical and historical aspects of kingship in a manner recalling the intellectual, courtly culture of what has been termed the Iranian Intermezzo, that era between the decline of the ‘Abbasid caliphate and the arrival of the Seljuks when Iranian dynasties flourished and New Persian or Farsi, written in Arabic script, emerged. It seems extremely improbable that Yusuf would have sought wisdom from a local Armenian lord but at some point it clearly held meaning to locate him in this context. Yet Gagik is also portrayed writing to the patriarch of Constantinople on a range of ecclesiological matters. When taken together these artistic and literary encounters advertise interaction and engagement rather than singularity or isolation.

Gospel book (1386), copied and illuminated by Petros the monk, Monastery of Manuk Surb Nshan, K‘aiberunik. J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

As the exhibition at the Met reveals, Armenian art can therefore be situated in a global context. A significant number of manuscripts from the scriptoria of Hromkla and Skevra in Cilician Armenia in the 12th and 13th centuries reflect interaction with both Byzantine and Western artistic traditions. The introduction of gold backgrounds and the wearing of imperial regalia are illustrative of the first – as depicted in the Gospel Book of Lady Keran and Levon II which also follows Byzantine imperial precedent in having the newly married couple being blessed by Christ and his angels; the incorporation of the evangelist symbols and the Lamb of God are indicative of the second. Other manuscripts attest more modest, local contexts, as shown in the endearing self-portrait of Petros the monk and his three students in a late 14th-century manuscript from a monastery north of Lake Van. Petros is depicted handing his inkpot and pen to his pupil Mkrtich, symbolising the transmission of scribal skills to the next generation; two other younger pupils, T‘uma and Simeon, are hard at work in the lower register, smoothing out the paper in preparation using heavy flat-bottomed burnishers.

The vibrancy and variety of Armenian artefacts in the exhibition reflect the longstanding traditions of engagement with, and service to, regional and imperial authorities – Roman and Persian, Byzantine and Islamic, Seljuk, Latin and Mongol, Ottoman and Safavid – on the part of the political elite. These features of Armenian art also reflect the migration of Armenians across the regions and cities of the premodern Middle East, both under compulsion and through choice, often reflecting commercial networks. Frustratingly the relationship between Armenian merchants and cultural production cannot be traced in the early medieval period. A ninth-century mosaic glass bowl excavated at Dvin points to commercial ties with Iraq although the possibility that it arrived in Dvin as a gift cannot be excluded; the millefiori technique, previously popular around the Roman Mediterranean until the second century, resurfaced unexpectedly in ‘Abbasid Iraq after a hiatus of several centuries. The gold jewellery found at Aygestan outside Dvin in 1936 includes items reflecting Byzantine and Fatimid manufacture, again attesting the city’s cosmopolitan character and commercial ties. The earliest extant manuscript, a Gospel book, to be commissioned by an anxious merchant, the self-professed unworthy and sin-serving Kirakos, was completed in 988/89. It may be no coincidence that Armenian scriptoria began to be attested in cities such as Theodosiopolis (modern Erzurum) and Melitene (Malatya) at this time and that connections between commerce, cities and artistic patronage developed thereafter, persisting after the eclipse of almost all the Armenian polities and lordships at the end of the 14th century. This shift can be explored through studying the art and culture of Armenian communities such as those in Kaffa in the Crimea and L’vov in Ukraine in the 15th and 16th centuries, or New Julfa in the 17th century. Hakob’s depiction of the Creator is unique and may reflect an image of the Buddha brought back from India or China. Although much of this commercial activity is hard to trace, let alone quantify, before the 17th century, the wealth generated made a significant contribution to Armenian artistic and cultural production, both directly through commissions and indirectly through the building of churches and the endowment of monasteries with rural and urban properties purchased through the profits of trade.

Crescent-shaped earrings, 11th century, found at Aygestan, outside Dvin, Armenia. History Museum of Armenia, Yerevan.

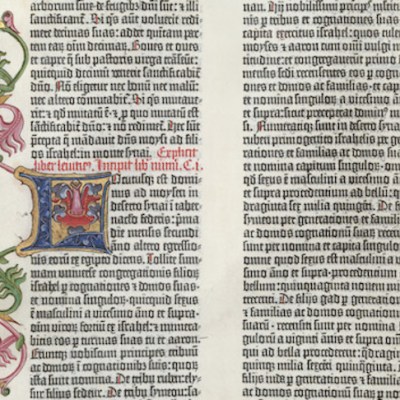

It was as a result of these same commercial networks that Armenian printing really began to develop in the middle of the 17th century. The first Armenian-language Bible was printed in Amsterdam in 1666 under the direction of bishop Oskan Erevants‘i of New Julfa and financed by three wealthy khojas from that community. It was embellished with hundreds of woodcuts by the Dutch artist Christoffel van Sichem the Younger. This is often viewed as a key moment in Armenian cultural history, marking the transition from the premodern to the early modern era. Yet Armenians continued to commission illuminated manuscripts throughout the 17th and 18th centuries and beyond in large numbers. This preference has much to tell us about Armenian identity and the close relationship with the Armenian past.

‘Armenia!’ is at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York until 13 January 2019.

From the September 2018 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.