When you wander a little off the beaten track at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, you may find yourself in an 18th-century French bedroom, or in the Frank Lloyd Wright room, or the poignant Damascus Room, with its Arabic inscriptions and splashing fountain. At the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, recent reinstallations include a Dutch wonder cabinet on a grand scale. At the Art Institute of Chicago, the perfectly miniaturised Thorne period rooms are ever-popular. One doesn’t have these diorama experiences at the Louvre or London’s National Gallery, or in the Prado. Is it a particularly American practice, to shape a fine arts museum as a procession through periods of history understood through decorative arts in architectural installations? The museum-goer who has wondered about this will find much to consider in Kathleen Curran’s book The Invention of the American Art Museum: Culture to Kulturgeschichte, 1870–1930.

Curran traces aspects of the US history of putting composite installations and period rooms in fine arts museums back to certain practices in German, Swiss, and Scandinavian institutions, such as the Schweizerisches Landesmuseum in Zurich, Munich’s second Bayerisches Nationalmuseum, the Germanisches Nationalmuseum in Nuremberg, and Wilhelm von Bode’s installation of the Kaiser-Friedrich-Museum in Berlin. Some of these institutions were founded as regional history museums with a mission of didactic preservation more like the Smithsonian, but Curran is interested in the way that fine arts museums borrowed ideas from these German historical institutions. There, the installations of rooms and artefacts, and the architectural designs favoured by their curators, gave viewers historical context, offering, as Curran puts it, ‘a seemingly paradoxical combination of atmospheric setting and scientific order’. This appealed to the newly professionalising museum administrators of the United States around the turn of the century – people like Wilhelm Valentiner, Henry Watson Kent, and Joseph Breck – who wanted to offer their visitors an education at once aesthetic and historical. Curran draws attention to a shift in US museum thought: the new idea was to combine what had been two kinds of museums – that for fine arts, which modelled itself on the picture galleries of the Louvre, and that for industry and craft, which modelled itself on the technical and materials-oriented displays of the South Kensington Museum (now the V&A).

Curran prefers German intellectual history, and perhaps assumes that her readers will already know the further histories of period rooms and composite installations that are to be found by tracing Italian lineages, or Native American ones, or British, Mexican, Spanish, Egyptian, Dutch, Syrian, Indian, Japanese, Greek, and French ones, all of which have had their effects on the US museums she discusses. As I read Curran’s account of the design of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, and of the influence of a visit the MFA’s directors made to the Hessisches Landesmuseum Darmstadt in 1904, I found myself mentally walking around the edge of the Fenway to the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum (which had opened in 1903, but is not mentioned in Curran’s account of the formation of the MFA).

Gardner had her sense of composite installation from sources including the Bargello Museum in Florence, the Wallace Collection, the private homes of Italian and British aristocracy, and also from a recent influx of Japanese art to Boston. It was at least a part of her idea that the people of her city should have access not only to isolated works, but also to a living relationship to works of art brought about by seeing combinations of paintings and tapestries, ceramics, and cassones; by imagining living in the rooms, as she herself did. Gardner’s was a complicated, and perhaps peculiarly American position. Unlike the European aristocrats whose houses were full of art she admired, she, like the other Gilded Age collectors, built a collection simultaneously intended for her private use and for a public purpose. Gardner’s chosen works were ones that could induce a state of reverie – not prayerful or historical, but aesthetic, intimate and, perhaps, also acquisitory.

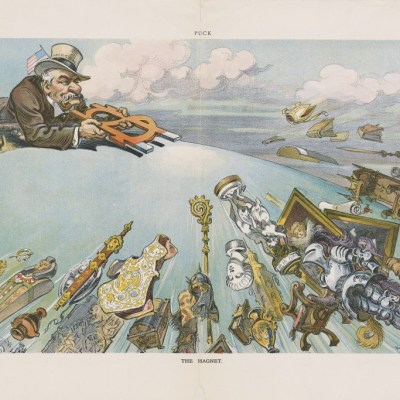

Kathleen Curran does not consider private museums such as the Gardner, the Frick, and the Barnes; the story that interests her is more about curators than collectors, and about museum design rather than the particular objects housed. But even at larger museums, much of what the curators and architects had to work with was first purchased by influential collectors and board members – by Andrew Mellon, Benjamin Altman, Arabella Huntington, John G. Johnson, Bertha Palmer, J.P. Morgan, Robert Lehman, and a score of others – under a peculiar rubric: ‘What would I like to have in my house and what do I think Americans ought to have as part of their experience of the art of the ages?’

If there were a museum of museums, in which the major museums of the world were represented by period rooms, then those for the Louvre would reflect Napoleonic history; those for the British Museum the history of the British Empire; the German Kulturgeschichte rooms would reflect the intellectual and economic climate of Bismarck’s German State, and those for the United States would show an odd mercantile oligarchism, with its blend of selfishness and philanthropy.

Along with its many weaknesses, one power of the American system (if such there is), was that its collectors had all had, individually, the experience they anticipated for museum-goers: that of growing up with the sense that all this was beyond their reach, then of discovering that art could, with strain and complexity, be a part of the daydreaming ordinary life of an ordinary person.

The Invention of the American Art Museum: Culture to Kulturegeschichte, 1870–1930 by Kathleen Curran is published by Getty Publications.

From the December issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.