Gerald Laing’s star, so long somewhat eclipsed, is rising. This is an artist who stood at the forefront of British Pop Art – and was one of the few, along with David Hockney, who saw success on both sides of the Atlantic – but who has only recently begun to regain the international recognition of his early career. Perhaps his fall from grace was due to the fact that he became disenchanted with Pop and abandoned it almost as quickly as he took it up, placing himself first in the vanguard of minimalist sculpture and then, in an extraordinary volte-face, relinquished that in favour of an increasingly retardataire figuration. Unforgivable. Unclassifiable. It could not have helped that he distanced himself by upping sticks and leaving New York in 1969 to live in the Scottish Highlands.

In 2014, three years after the artist’s death and following a run of Pop retrospectives, Christie’s auctioned his most famous image: Brigitte Bardot (1963). The source for this huge painting was the logo on the request for entries for the 1963 Young Contemporaries exhibition – a black and white photograph of the siren of the ’60s screen on to which a black circle had been superimposed. Laing audaciously appropriated the image, meticulously painting the grid of dots in emulation of the half-tones of print reproduction. He did this at much the same time as Roy Lichtenstein – seemingly quite independently – while still a student at St Martin’s School of Art. It was from his studio there, even before its paint was dry, that the actor Roddy Maude-Roxby acquired the canvas for £40. Laing’s submission was accepted, and duly made the show’s poster. Christie’s sold the canvas for £902,500.

That record was broken last year when the same auction house sold Commemoration of 1965, one of his series of bikini-clad girls drawn – literally – from the pages of magazines. That changed hands for £1.2m.

Study for ‘Brigitte Bardot’ (1963), Gerald Laing. Courtesy the Fine Arts Society

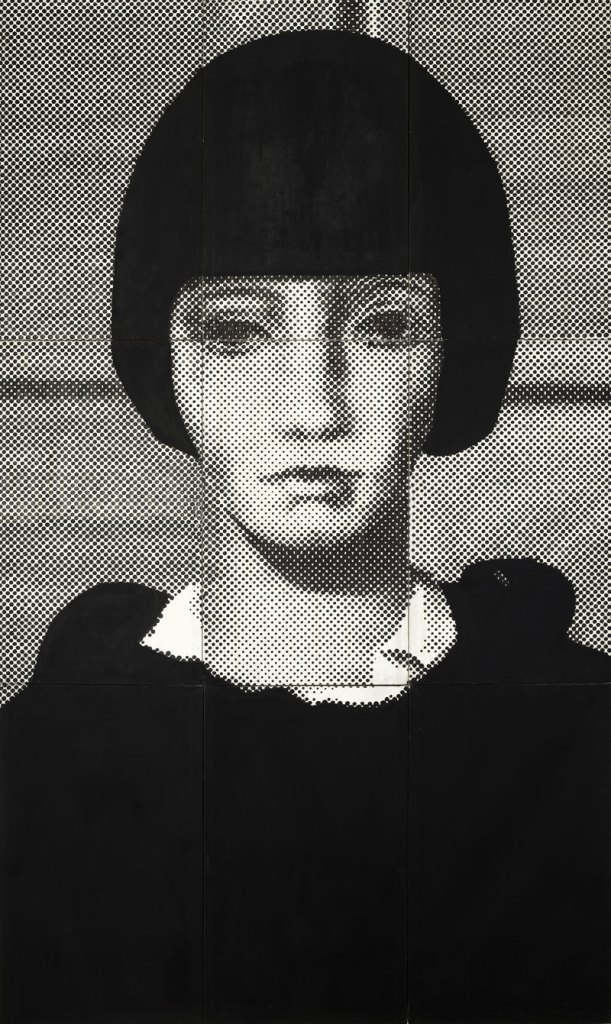

This autumn, Laing’s dealers, The Fine Art Society, have staged a long-planned retrospective of the artist’s work (until 13 October) to coincide with the publication of the catalogue raisonné by the artist’s estate. It features everything from the small tracing that was Laing’s first study for Brigitte Bardot to the monumental nine-panel Anna Karina (1963). Karina was the ingénue film star wife of Jean-Luc Godard and had starred in Vivre Sa Vie (1962), a 3cm-high newspaper advertisement for which was the source of this colossal 3.6m-high work. Laing and his friends hoisted it like a billboard on to the walls of St Martin’s. Later, the artist always refused to sell it.

Anna Karina (1963), Gerald Laing. Courtesy The Fine Art Society and David Knight

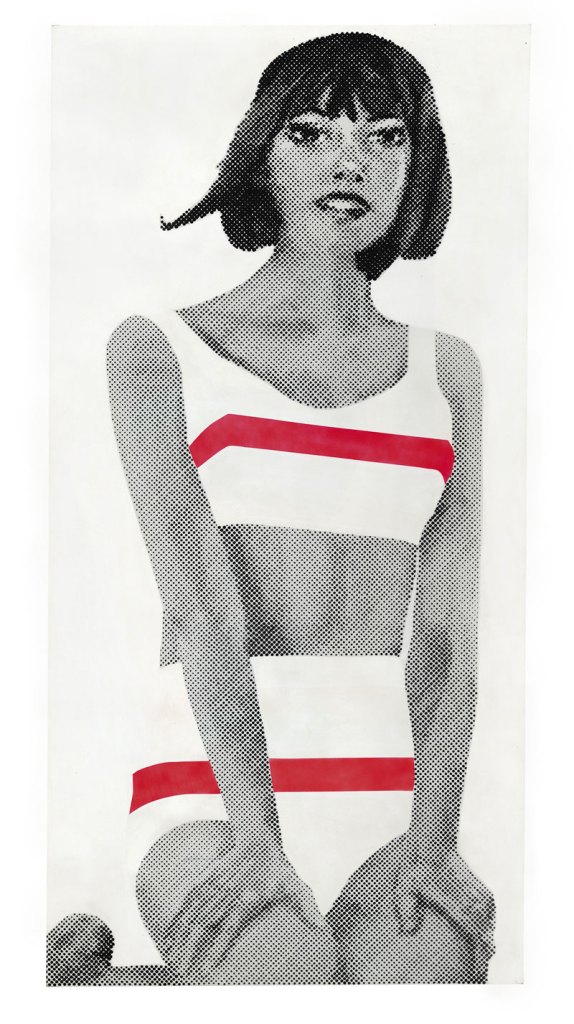

Unfortunately, the catalogue raisonné has been delayed. Unexpectedly, one of the show’s anticipated star works is also absent. Beach Wear (1964), published in the catalogue, is now to be found at Christie’s Post War & Contemporary Art evening sale on 6 October, part of a group of works focusing on the female form. Standing nearly 2.5m high, this is the largest painting of the beach girls series. Here the image is taken from an advertisement on the cover of Eva, the grid of dots contrasting with the bright flat colour of her striped bikini. It comes with expectations of £1m–£1.5m – and a third-party guarantee. Similarly, Anna Karina bears a seven-figure price tag.

Beach Wear (1964), Gerald Laing. Image courtesy Christie’s

At St Martin’s, Laing was taught by Richard Smith, who had just returned from a Harkness scholarship in New York and was exploring advertising and mass-media imagery in his own work, as well as in lectures and screenings at the ICA. Laing described how he looked for an appropriate systematic approach to tackling this imagery and found it in ‘the crude but powerful printing processes used in poster advertisements’. He found himself transfixed by ‘the dots and lines and cacophony of form and colour visible at a short range, and the reassuring integrity of the image at a distance’. He explained: ‘So strong were these to our eyes, accustomed as they were only to the peeling stucco of wartime neglect, that they seemed to eclipse reality and acquired the pungent authority of the icon.’

Laing left for New York where Robert Indiana employed him as a studio assistant. After his return, the dealer Richard Feigen found Laing’s paintings in Indiana’s loft, suggested he move permanently to New York and offered him the first of a series of shows there and in Los Angeles, which accounts for so many of his Pop paintings – and silkscreen prints – of celebrities, girls, cars, and astronauts remaining in the US. Oddly, Laing’s detached, clean-edged style was more aligned to American Pop than it was to the more painterly narratives of the English strain, and was so attuned to its zeitgeist that his brilliant, irregularly shaped Lincoln Convertible of 1963–64 at the FAS, based on two frames of Kennedy’s assassination published in Life magazine, eerily parallels Warhol’s death and disaster series. It was considered ‘too raw’, however, to exhibit to the American public in 1964, and spent nearly 30 years folded up in a garden shed in New Jersey, almost lost forever. It is not for sale.