Elizabeth Rigby, the writer and art historian, lived in Edinburgh in the 1840s where she was photographed by the calotypists David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson. Later, as Lady Eastlake – having married the Keeper of the National Gallery in London – she wrote an important essay in 1857 on the art of photography, noting how it ‘had made but a slow way in England; and the first knowledge to many even of her existence came back to us from across the Border. It was in Edinburgh where the first earnest, professional practice of the art began.’

Lady Elizabeth (Rigby) Eastlake, 1809–1893 (c. 1845), David Octavius Hill (1802–70) and Robert Adamson (1821–48). Scottish National Portrait Gallery

J.L.M. Daguerre, the entrepreneur and painter who had made four dioramas of Scottish scenes in the 1820s, announced the discovery of his photographic process in Paris in 1839; Edinburgh was second only to the French capital in importance in the early history of photography. In their magisterial survey of the development of the medium in Scotland in the mid 19th century, Sara Stevenson and A.D. Morrison-Low convincingly argue that the early success of a process that combined the sciences of optics and chemistry with artistic insight was the legacy of the Scottish Enlightenment. It is significant that Henry Fox-Talbot, inventor of the calotype – the negative-positive process on paper – communicated his discoveries to the Edinburgh physicist Sir David Brewster, who then encouraged its development. Perhaps it is equally significant that the industrialist James Nasmyth should have taken up the calotype.

Photography in Edinburgh in the early days now seems to be dominated by the productive partnership between the painter Hill and the chemist Adamson, but there were other early exponents of the calotype. John Muir Wood worked in the capital and in other Scottish cities, and other numerous, often itinerant practitioners made small framed portraits using the single (reversed) image daguerreotype process. Some 1,500 photographers who were Scots or worked in Scotland in the first 30 years of photography have been identified and many of them brought to life in this monumental publication following decades of research. The authors note that their book was written in the run-up to the 2014 Scottish independence referendum: ‘Nationalist histories are often found to be protesting too much. Do we need a history of Scottish photography? Do we need one now?’ The answer must be a resounding ‘yes’. ‘Hill and Adamson invented social documentary photography. Instantaneous photography was demonstrated by Allan Maconochie, John Stewart and George Washington Wilson; David Brewster led the way to three-dimensional photography. An aesthetic for photography, which helped to inform and lead the older arts, was explored by individuals such as James Ross, Thomas Annan, Thomas Keith and Lady Hawarden.’ Furthermore, James Clerk Maxwell was investigating the possibilities of colour photography as early as 1859, while Mungo Ponton’s chemical discoveries in 1839 were ‘the basis not just of the carbon process, but of the later process printing techniques and the manufacture of circuit boards’.

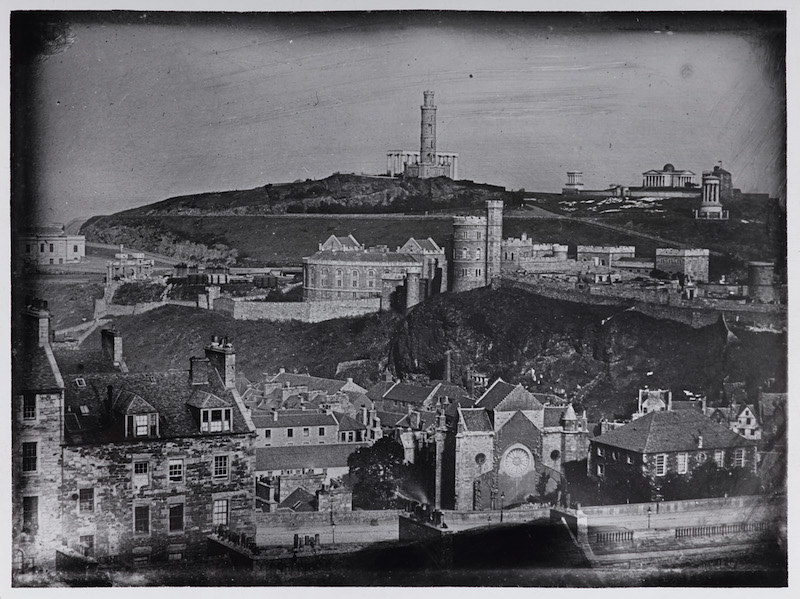

Daguerreotype showing Calton Hill from the High Street (c. 1840), attrib. to Thomas Davidson (1798–1878). National Museums Scotland

Edinburgh was not the only place in Scotland where photography flourished in the pioneering decades. St Andrews is recorded in early calotypes. In Glasgow there was Thomas Annan, best known for his records of the slums off the High Street in the 1860s. And in Aberdeen there was the hugely prolific commercial topographical photographer G.W. Wilson, in whose obituary it was observed that ‘Sir Walter Scott discovered Scotland with his pen, and George Washington Wilson rediscovered it with his camera’ – a camera he also took to England and elsewhere. Just as Scots made and ran the British Empire, so Scottish photographers travelled abroad, to Canada, India and Australia and, recording antiquities, to Egypt, Palestine, and China. The most famous of these Scottish itinerants is the Paisley-born Alexander Gardner, who moved to New York in 1856, and who worked for Mathew Brady and, later, was attached to the Army of the Potomac and responsible for some of the most haunting images of the American Civil War.

Daguerreotype showing the Observatory of Edinburgh and Playfair’s Monument from the South East, attrib. to Thomas Davidson. National Museums Scotland

Stevenson and Morrison-Low have been investigating, cataloguing, and writing about the history of Scottish photography for over three decades – publishing pioneering studies of both the science of photography and the important achievement of Hill and Adamson. As Graham Smith, Emeritus Professor of the History of Photography at St Andrews, notes in his foreword to this splendid book, ‘Had they lived elsewhere, they would have been designated living national treasures long before now.’ But I fear they have yet more to do. It is one of the frustrations of the book, lavishly illustrated though it is, that many of the early images mentioned or described in the text are not reproduced. Furthermore, it displays the bias of many books of photographic history in illustrating more images of people than ones of buildings and topography. Often, historians of photography are more interested in the techniques, in the cameras and the careers of the early photographers than in what their images actually show. I am, of course, reflecting my own bias as an architectural historian, but the fact is that Edinburgh is the best-recorded city in early photographs other than Paris and there is a wealth of enthralling early topographical calotypes in collections in both Edinburgh and Glasgow showing buildings which have now disappeared – like the Medieval Trinity College Church demolished to make way for Waverley Station, and The Mound before the National Gallery appeared.

Girl holding a portrait of a man, possibly her dead father, Ross & Thomson of Edinburg (1847–60). National Museums Scotland

One of the most covetable works of photographic history is Paris Et Le Daguerréotype, published by Paris-Museés in 1989. This reproduces the precise silvery plates made of streets and buildings in the Paris of Louis-Philippe by Daguerre’s process – some as early as 1839 and many showing Notre-Dame in great detail before Viollet-le-Duc got his hands on it. So please can National Museums Scotland publish a similarly lavish volume, entitled, say, Edinburgh and the Calotype, written by Stevenson and Morrison-Low, with the images of Hill and Adamson and others reproduced to a similarly high standard?

Scottish Photography: the First Thirty Years by Sara Stevenson & A.D Morrison-Low is published by National Museums Scotland.