The market in Korean ceramics peaked around 20 years ago as wealthy Koreans bought back their heritage. Since then, prices have dipped significantly and the value of these objects has diminished – but in the long term, interest is expected to revive

One of the most vivid illustrations of the capricious nature of value is the history of Japan’s love affair with Korean ceramics. In Japan during the late Muromachi period (1336–1573), the tea ceremony, once ornately practised as in China, turned away from elegance towards rustic simplicity. In a time of civil war, this more spartan wabi style was exemplified by the use of simple tea bowls, produced originally as rice bowls by country potters in Korea’s South Gyeongsang province.

During the Tenshō era (1573–92), these rough, creamy-brownish bowls – with their scorch marks from the kiln and wrinkled glaze – became highly prized symbols of favour, passed down from warlord to warlord and then through families. Today, the finest examples are designated national treasures in Japan. The most famous is the Kizaemon tea bowl, preserved in the Daitoku-ji temple in Kyoto. It became an object of veneration for generations of Japanese aesthetes and philosophers, influencing, through them, Bernard Leach, a pioneering figure in 20th-century British studio ceramics.

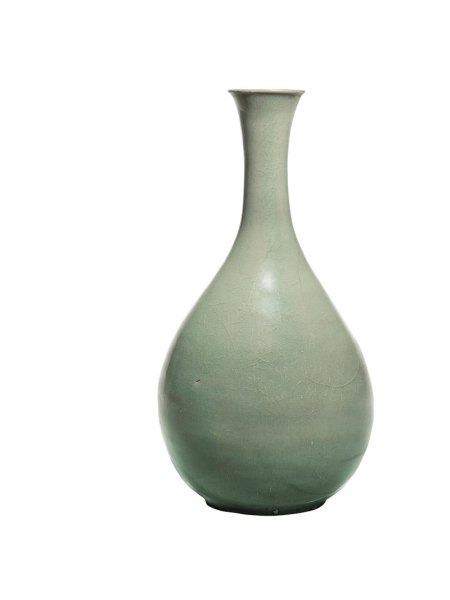

Bottle vase (12th century; Korean, Goryeo dynasty 918–1392). Sotheby’s Hong Kong, HK$1.6m. Courtesy Sotheby’s

That tea bowl is said to be priceless. But its ilk today, without such a provenance, has very little financial value. As Jeff Olson, director of Japanese art at Bonhams, says: ‘People put great stock in the history. Without it, these objects are worth much less.’ In 2013 at Christie’s New York, a simple Joseon stoneware tea bowl dating from the 16th century, with a white slip and greenish transparent overglaze, sold for a modest $4,750.

Henry Howard-Sneyd, Sotheby’s chairman of Asian Art, Europe and Americas, explains that the market in Korean ceramics is greatly diminished compared to its heyday in New York in the late 1980s and early 1990s, when wealthy Koreans, at last able to export their money, spent freely on their heritage, and Korean museums were busy buying back masterpieces exported over the centuries. There are, however, pockets of the market that remain active today – Howard-Sneyd describes this activity as ‘mostly private, conducted between Japan and Korea’. These days, once prize pieces have returned to Korea, they cannot be exported again. But when they do appear on the international market, they can fetch good prices. At Sotheby’s Hong Kong’s sale of Roger Pilkington’s collection of Chinese art in April, an elegant 12th-century Korean bottle vase from the Goryeo (or Koryo) dynasty (918–1392), with a beautiful sea-green celadon glaze, fetched HK$1.6m (£148,242). Howard-Sneyd comments that while for many years the Chinese have shown no interest in Korean ceramics, this does seem to be changing.

Goryeo wares represent the first pinnacle of achievement in Korean ceramics. During the 10th and 11th centuries, Korean potters were heavily influenced by Chinese production techniques. But in the 12th century, the Goryeo period saw the development of its own unique style of celadon, renowned for the greyish blue-green colour of its kingfisher glaze and its refined shapes. Potters also developed a distinct method for inlaying decoration and other patterning techniques – including incision, relief carving, impressing, openwork and sculpting. There are significant collections of such pots not just in Korea and Japan but also in America and Europe, including the outstanding Gompertz collection in the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge.

Wine bottle (late 15th century–early 16th century; Korean, Joseon dynasty, 1392–1897). Bonhams New York, $27,500. Courtesy Bonhams

Sebastian Izzard, a leading New York dealer, says: ‘Goryeo celadons have been coming to the West for 120 years. Now it is a very small part of my business.’ He warns that a pre-1970 provenance is key. For London dealer David Baker, it is the individuality of Goryeo vessels – each a separate one-off creation for the royal family and aristocracy with subtly varied decoration – that appeals. He believes that such works are today undervalued in comparison with the prices achieved 20 or so years ago. He currently has a characteristic late 12th-century Goryeo bowl, the exterior inlaid with a floral design, the interior with four cranes, for £4,500; a comparable – although admittedly exceptional – inlaid 12th-century Maebyong vase from the Goryeo dynasty fetched $717,500 at Christie’s New York in 1997. Baker is confident, however, that one day appreciation will revive.

By the end of the 13th century, repeated invasions from Yuan China had weakened the Goryeo court and its ceramics tradition. In the late 14th century the Joseon dynasty (1392–1897) saw the emergence of Buncheong ware: blueish-green stoneware covered in white slip under a transparent glaze, some with dark iron pigment decoration. These works had a more inventive character, and it is the more decorative examples that fetch good prices today. In March last year at Bonhams in New York, a wine bottle with iron-painted decoration from the late 15th or early 16th century achieved $27,500. And in April at Christie’s New York, a similar example, though with finer decoration, fetched $149,000 (estimate $140,000–$160,000). London-based dealer Jinsoo Park of Han Collection confirms that these objects appeal particularly to western audiences, but their manufacture was blighted at the end at the 16th century when the Japanese invaded Korea. Failing to conquer the peninsula in two separate campaigns, Emperor Hideyoshi’s troops kidnapped between 50,000 and 200,000 Koreans, including many skilled artisans, which had a lasting impact on pottery production in Japan.

Moon jar (18th century; Korean, Joseon dynasty, 1392–1897).

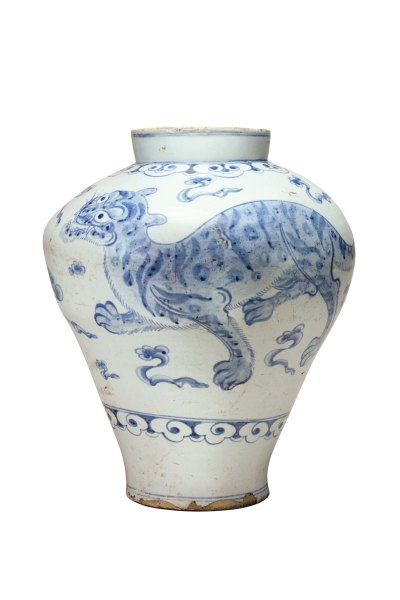

As the Joseon ceramic tradition recovered, the focus shifted to porcelain white wares. These had been fashionable since the 15th century, reflecting the severe Neo-Confucian values of the Joseon court. From the 17th century their popularity spread – both the pure white wares associated with the bulbous moon jars, fashionable in the 18th century, and those examples decorated with cobalt-blue, iron-brown or copper-red tigers and dragons. Jinsoo Park has a fine 18th-century moon jar available for £65,000. Once again, however, the highest prices are achieved by the most finely decorated pieces. It was an iron-brown decorated dragon jar that made the record price for a Korean ceramic in 1996 ($8.4m) at Christie’s New York – then also the auction record for a work of Asian art. Today, according to Takaaki Murakami, a specialist at Christie’s New York, the more unusual the motif, the higher the price. He cites the magnificent Joseon blue and white porcelain jar with a fierce tiger and mythical lion, dated to the late 18th or early 19th century, which sold at Christie’s New York in April for $965,000 (estimate $150,000–$250,000). ‘If we can find something important,’ says Murakami, ‘then we can find a buyer.’

Jar (19th century; Korean, Joseon dynasty, 1392–1897). Christie’s New York, $965,000. Christie’s Images Ltd.

From the November issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.