The portly, balding figure of South African artist William Kentridge, in trademark button-down white shirt and black trousers, is a familiar one in his own work. In the 2012 animation Anatomy of Melancholy, displayed as part of ‘William Kentridge and Vivienne Koorland: Conversations in letters and lines’ at Edinburgh’s Fruitmarket Gallery, we see it racing through the pages of Robert Burton’s Anatomy of Melancholy (1621). The book operates like a child’s flip book, with Kentridge trapped in its pages; just as Burton was, revising and republishing it for much of the rest of his life. What the curator Tamar Garb calls Kentridge’s ‘bookishness’ can be both enriching and restrictive.

Kentridge is everywhere at the moment. Working across prints, animation, video, sculpture, opera, theatre; with an exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery; a production of Berg’s Lulu at the ENO; and Paper Music, a song and film cycle at London’s Print Room. The works themselves contain multitudes of influences and materials. Yet they often resolve into the figure of the bookish artist.

The broadest political questions, such as the nature of post-apartheid South Africa, are understood through the prism of his individual experience (Kentridge’s father Sydney represented Nelson Mandela at his 1956 treason trial). Another animation, Felix in Exile (1994), considers how apartheid will be remembered. Not long before South Africa’s first general election, Felix, a half-naked man who bears a suspicious resemblance to Kentridge, sits alone in a foreign hotel room, looking at the landscapes on the walls, eventually joining an imagined dialogue with their artist, Nandi, who has made a record of the regime’s atrocities, until she dies: one more victim of apartheid.

Installation view of Notes Towards a Model Opera at Fruitmarket Gallery. Courtesy the artist

Even the most intellectually omnivorous artists benefit from being drawn out of themselves and into a conversation; which is what this small but exacting exhibition manages so well, tracing the preoccupations and practices Kentridge shares with fellow South African artist, Vivienne Koorland – a friend since university days. Whereas Kentridge is promiscuous in his choice of medium, Koorland tends to work with large canvases, and she opens the conversation even wider. Quotation for her is often part of a process of ventriloquising lost voices. Vive Maman (1987) is a charcoal copy of the rendering of a pot of flowers as a birthday wish for his mother, by a young French boy who later died at Auschwitz. It resembles a funeral wreath, drawn over a collection of pages from newspaper coverage of the Holocaust. The Divide (2013), a short story about a boundary dispute by Rabindranath Tagore, painted on to squares of linen, explores what happens when you replace figuration with words. The answer is, not much: you just become very frustrated when you can’t make out key passages in the story because of the messily painted text.

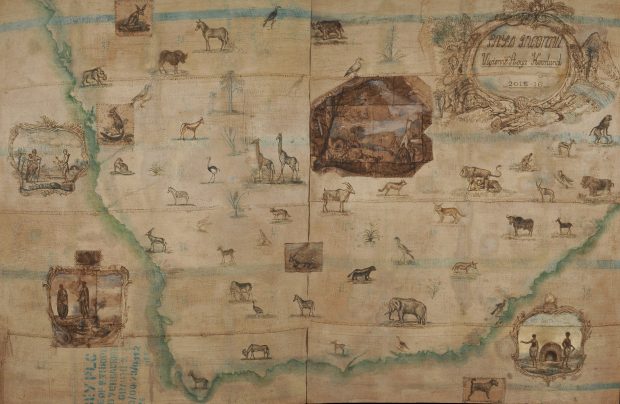

More successful is Koorland’s use of old maps. A map may not be a text as such, but it is, as Kentridge points out, ‘an idea’. Though presented as objective, maps are a means of appropriating, organising, and defining a place and its history. The first room of the exhibition is dominated by the huge Pays Inconnu (2016), an outline map of South Africa based on a hunting map composed for Louis XVI. The original imagines South Africa as the King’s personal playground, dotted with indigenous animals Louis might kill for sport. Koorland makes this South Africa her own paradise, adding her pet dog to the menagerie. In Kentridge’s three-screen video installation, Notes Towards A Model Opera (2015), projected revolutionary maps of China and Maoist commandments are overshadowed by the individual skill and exuberance of the South African dancers waving red flags on point in front of them; another effective rebuke to political and imperialist presumptions.

Installation view of works by Vivienne Koorland at Fruitmarket Gallery. Courtesy the artist

Maps and texts provide what Garb calls the ‘semiotic residue of the past’, and both artists incorporate this palimpsest approach into their technique in a very practical fashion. Koorland paints not only on the pages of old books but also linen, burlap, and even used sacks of Ethiopian coffee beans. Kentridge alters a single drawing for his animations, rather than the normal practice of drawing hundreds of minutely altered frames, so that each frame carries the literal residue of its past. The animation Carnets d’Egypte: East Rand Proprietary Mines Ltd., Central Administration (2010) shows him deconstructing one of these palimpsests. We watch as he peels back layers of a landscape painted into the ledger book of an old colonial mining company, until a final image is revealed: the figure of the artist: portly, balding, in trademark white button-down shirt and black trousers.

‘William Kentridge and Vivienne Koorland: Conversations in letters and lines’ is at Fruitmarket Gallery, Edinburgh from 19 November 2016–19 February 2017.