This review of A Catalogue of the Pictures and Drawings at Wilton House by Francis Russell (Archaeopress Publishing) was first published in the January 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Marvelling at Anthony Van Dyck’s Pembroke family portrait in the Double Cube Room at Wilton House near Salisbury is one of the truly great experiences to be enjoyed in a British country estate. But as this invaluable catalogue demonstrates, this splendid painting is only one of many to be studied in the collection it dominates. Like many venerable collections, it contains highs and lows, curiosities and stars; it is, however, the ensemble and the way it conveys shifts in taste and the interests of particular patrons that proves so fascinating.

This catalogue is old-fashioned in the best sense: it tells you what you need to know, it is written with elegant concision and its author has a breadth of knowledge that allows him to wander with ease from the art worlds of Renaissance Rome or the Dutch Republic to Georgian London. There is a detailed introduction to the family of the earls and countesses of Pembroke as collectors and patrons, which emphasises in particular the achievements of three generations. First, Philip Herbert, the 4th Earl (1584–1650), who commissioned the monumental Van Dyck portrait and was a close ally of Charles I; the king gave him a book of portrait drawings by Holbein in exchange for Raphael’s St George and the Dragon (now in the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.). The second very important figure in terms of the evolution of the collection was Thomas, the 8th Earl (1656–1733), a friend of John Locke, who undertook an early Grand Tour to Italy in the 1670s and acquired significant Old Masters, the most extraordinary of all being the late 14th-century Wilton Diptych (National Gallery, London). Third in this line of collectors was Henry, the 10th Earl (1734–94), whose tastes were also shaped by an Italian tour and who became an important patron of contemporary artists. The story does not end there, since portraits continued to be commissioned and, indeed, have been reunited with the family recently: for example, last year a pastel by Francis Cotes from 1762 of Mary, widow of the 9th Earl, was acquired.

This catalogue is old-fashioned in the best sense: it tells you what you need to know, it is written with elegant concision and its author has a breadth of knowledge that allows him to wander with ease from the art worlds of Renaissance Rome or the Dutch Republic to Georgian London. There is a detailed introduction to the family of the earls and countesses of Pembroke as collectors and patrons, which emphasises in particular the achievements of three generations. First, Philip Herbert, the 4th Earl (1584–1650), who commissioned the monumental Van Dyck portrait and was a close ally of Charles I; the king gave him a book of portrait drawings by Holbein in exchange for Raphael’s St George and the Dragon (now in the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.). The second very important figure in terms of the evolution of the collection was Thomas, the 8th Earl (1656–1733), a friend of John Locke, who undertook an early Grand Tour to Italy in the 1670s and acquired significant Old Masters, the most extraordinary of all being the late 14th-century Wilton Diptych (National Gallery, London). Third in this line of collectors was Henry, the 10th Earl (1734–94), whose tastes were also shaped by an Italian tour and who became an important patron of contemporary artists. The story does not end there, since portraits continued to be commissioned and, indeed, have been reunited with the family recently: for example, last year a pastel by Francis Cotes from 1762 of Mary, widow of the 9th Earl, was acquired.

The 331 catalogue entries are arranged according to the order in which works entered the collection, which gives a sense of its organic, sometimes quirky growth; 126 colour plates follow. It is assumed that biographies of artists can be consulted elsewhere, and throughout there is generous acknowledgement of other scholars’ views. Full use is made of historic inventories, visitors’ accounts and older catalogues, the first of which, by Carlo Gambarini, appeared in 1731.

Elizabeth, Countess of Pembroke, with her son, George, Lord Herbert, later 11th Earl of Pembroke, (1764–67), Joshua Reynolds. Wilton House, Wiltshire. Photo: Dominic Brown; © Wilton House

Certain works stand out. These include the Raphael chalk study of the head of a cardinal, an extraordinary rarity, assumed to have been acquired by the 8th Earl. Dating from 1513–15, it presents an intriguing problem, since the sitter’s identity remains unconfirmed, although candidates have been proposed; it was presumably a sketch from life for an unrealised oil portrait. Other great drawings include a Holbein portrait of Lord Bergavenny of 1532–35, mistakenly identified in the past as a depiction of Thomas Cromwell, and among baroque sheets a complex Rubens study after Barocci of the martyrdom of St Vitalis, as well as an especially fine depiction of a young man by Carlo Dolci, from the 1630s.

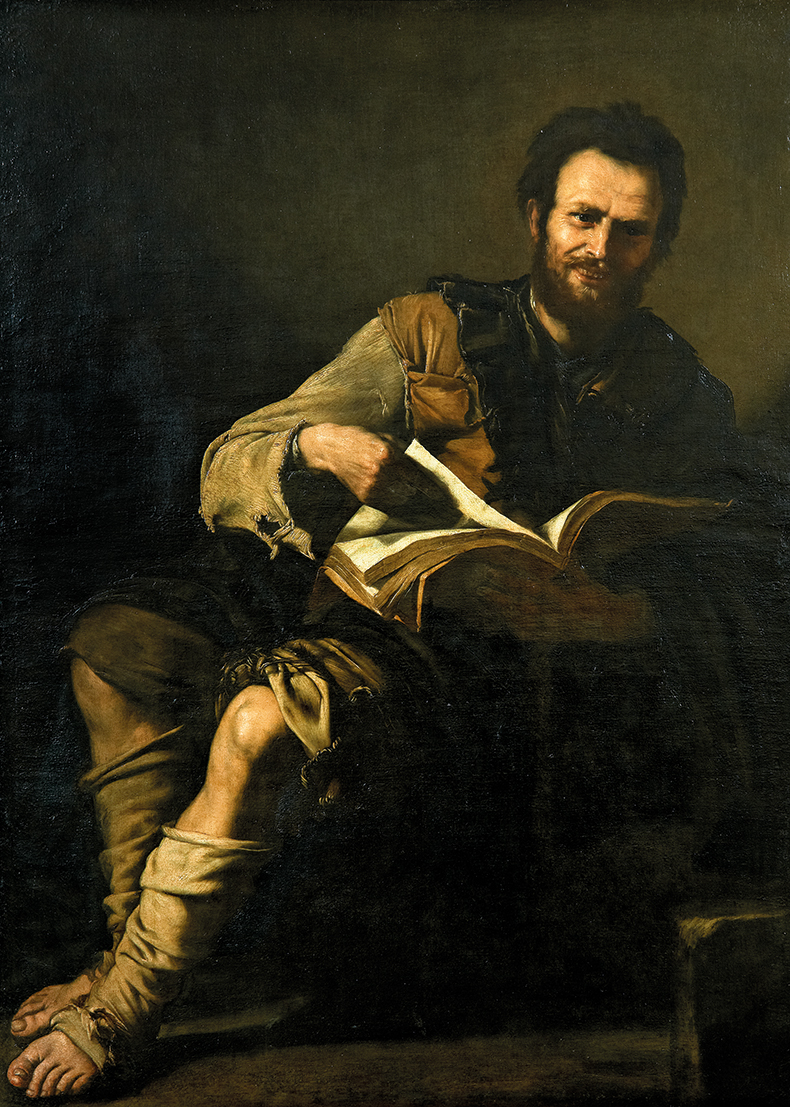

Aside from the superb Van Dycks, which include an intense and sensual portrayal of the Countess of Castlehaven, 17th-century paintings in the collection are perhaps dominated in qualitative terms by two canvases. The first of these is An Old Woman Reading: the Prophetess Hannah which was long considered to be by Rembrandt and now hovers around him, being attributed to Jan Lievens and a Rembrandt associate: the meticulous precision of the face contrasts with the breadth of impasto used to define the book that is pored over. The other stellar work from this period, which also has a bookish theme, is Ribera’s Democritus – the philosopher gently smiles and directly engages with the viewer, his studies being alluded to by the text he clasps, his humility by his ragged clothes. It has a Medici provenance, and must be one of the earliest works by the artist to have reached Britain, where it is first recorded in 1728.

Democritus (1635), Jusepe de Ribera. Wilton House, Wiltshire. Photo: Dominic Brown; © Wilton House

Notable among the collection’s great 18th-century acquisitions and commissions is a fine group of Richard Wilson landscapes. The Italian vedute, of subjects such as Ariccia, were acquired by the 10th Earl and presumably inspired his commission from the painter of six views of Wilton itself, which show it from different vantage points and in different climatic conditions, such as before a Claudian sunset and about to be engulfed by a storm; they have an honourable place in the evolution of portraits of country houses. The 10th Earl was equally discriminating when he determined how portraits of family members might best be commissioned, and the result was a wonderful sequence of works by Joshua Reynolds. Especially tender and thoughtful is the portrayal of Elizabeth, Countess of Pembroke, and Lord Herbert; she wears a delicate violet dress and gold scarf and holds her young son close, as if the sitting has interrupted their reading. Portraits inevitably contribute in interesting ways to the family history strand of the collection: they stretch back to those owned by the 1st Earl in the 16th century and on to refined canvases by Knapton, Batoni, Beechey and Lawrence, although perhaps none match the works by Reynolds for impact. A delicate coda to such works is provided by a slight sketch by David Hockney from 1966 of the 17th Earl.

Wilton House and its remarkable collection has recently been particularly well served by new publications; in addition to this catalogue, there has been the sculpture catalogue by Peter Stewart (2020), and John Martin Robinson’s book on the architecture, interiors and history of the family (2021). Collectively they make you want to travel to Salisbury and become reacquainted with such an extraordinary collection in its magical home.

A Catalogue of the Pictures and Drawings at Wilton House by Francis Russell is published by Archaeopress Publishing.

From the January 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.