From the June 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

The Gulf Stream, a late work that Winslow Homer painted in 1899 and reworked seven years later, is the centrepiece and fulcrum of the Metropolitan Museum’s current survey of the artist. A Black man lies on the deck of a small boat as it rears up in stormy waves. The mast has snapped; long green stalks of sugar cane are strewn about; sharks gather in the foreground. Its elements are spare, but it shows an artist richly immersed in his moment.

Homer has long been regarded as a painter of chilly New England, but he spent winters in the South and produced picturesque watercolours of the Bahamas, Bermuda, Florida and Cuba: scenes of oranges ripening in the sun; local girls sheltering under palm trees. The Gulf Stream is one of the major paintings that rose out of those experiences and with it the Met makes the case for shifting our sense of Homer, from flinty observer of the Civil War and laureate of the perils of the sea, to that of a figure who navigated the historically freighted networks of the Atlantic world. This isn’t an ocean with a few human dramas on its shores, but one that supported centuries of trade and travel, slavery and empire. This is a new Homer for our time.

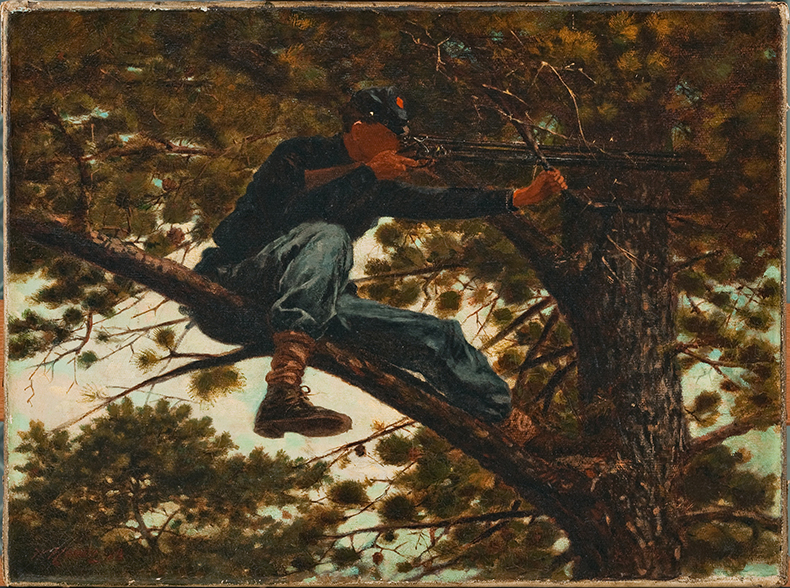

Homer began his career as an illustrator in 1859 and he would maintain that work intermittently for nearly 30 years. Most significantly, he travelled south with the Union Armies during the Civil War, covering the conflict for Harper’s Weekly, and from those journeys came early triumphs on canvas such as Prisoners from the Front (1866), in which a young Union officer inspects the enemy. He had an illustrator’s eye for detail – a sniper’s eye, you might say: Sharpshooter (1863) depicts a Union soldier perched on a branch, picking out a distant target. Snipers were first used during the Civil War and they dramatically changed the nature of battle; Homer later reflected that their activity was ‘near murder’.

Sharpshooter (1863), Winslow Homer. Portland Museum of Art, Maine. Courtesy of Meyersphoto.com

If details enliven his pictures, they are most often foils for universalising themes, historical anchors set against timeless human struggle and this universalising tendency increasingly takes hold of Homer’s art as it matures. It’s the driving force of the extraordinary seascapes he painted while living in Cullercoats in the north-east of England in 1881–82, a town that had evolved into a popular artists’ retreat and tourist attraction, and he continued in this vein in Prouts Neck, Maine. Fishermen drift, lost at sea; women, forlorn, stand on misty shorelines and scan the horizon. In some of the most extraordinary and erotically charged pictures, musclebound hunks pull waterlogged maidens to safety from the waves. The Life Line (1884) shows a man carrying a woman across a winch suspended over crashing waves, their bodies stretched across each other to form a mid-air pietà. There’s little history here and lots of sex, and a while ago it prompted some questing scholars to speculate on Homer’s appetites.

His two visits to Europe undoubtedly made him bolder in his artistic experiments. The Barbizon School enriched his landscapes; Turner lent turbulence to his seascapes. One senses that, with time, this modernising ambition also served to clear away the moralising of his earlier vignettes. Human figures fade and in the late works only waves remain – opportunities for Homer to exhibit his confidence as a modern painter while also retaining the spirit of noble struggle that permeated the earlier scenes.

The Gulf Stream (1899), Winslow Homer. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The Gulf Stream is not the best of Homer’s pictures, nor the most intriguingly weird: the sharks look like extras from Jaws. But its central figure exudes that mix of determination and resignation that is pure Homer. It deserves its position in the show not least by virtue of its balance of anecdote and grand theme. The Black figure and sugar cane allude to trade and colonies and slavery while the waves set them adrift from history and human conflicts. But is allusion equal to argument? Is sugar cane on a boat in the Caribbean a comment on colonialism or a mere observation, a glimpse?

In constructing a new Homer, it can feel that the Met’s curators want to frame him as somehow engagé – which doesn’t always convince. Defiance: Inviting the Shot before Petersburg (1864) shows a Union soldier cavorting recklessly above the parapet before Confederate troops; beside him, reduced to supporting cast, is a Black banjo player depicted in the manner typical of minstrel caricatures. Then in The Cotton Pickers (1876), two Black women are given centrality, nobility and personality and, for once, Homer seems forthright: the Civil War might have abolished slavery but it hadn’t changed the facts of inequality and segregation in the South, and the anger and boredom carved on the women’s faces register their feeling. Is this a protest? Perhaps, but it wasn’t one strong enough to dissuade a British cotton merchant from buying it.

The Cotton Pickers (1876), Winslow Homer. Photo: © 2021 Museum Associates/LACMA; licensed by Art Resource, NY

No artist can escape some engagement with the conflicts of the moment, some position-taking, and it’s this that the Met’s show wants to throw into relief. Sometimes it feels misplaced and the wily Homer slips the chains; other times it feels exactly right, even if the answers can’t be read from the pictures themselves but lie in contemporary reactions, in the fine print of reviews and the muttering at exhibitions. This different optic, this new scrutiny, can also yield fresh thoughts in the unlikeliest places. Even in the late work, where there is nothing but wind and waves, you find yourself wondering what details Homer is pushing out of the frame and who preferred it that way. The figure lying on the swaying deck in The Gulf Stream could probably tell you.

‘Winslow Homer: Crosscurrents’ is at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, until 31 July.

From the June 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.