Mundane objects take on a mind of their own in the work of Woody De Othello. The artist turns clocks, telephones and even taps into oversized clay sculptures that seem distinctly animistic. Misshapen vessels are adorned with human body parts, while still-life paintings bear a dreamlike quality. Both kinds of work can be seen in his first solo exhibition in the UK: ‘Woody De Othello: Faith Like A Rock’, at Stephen Friedman Gallery in London from 8 March–13 April.

A Plea for Mercy (2024), Woody De Othello. Photo: Phillip Maisel; courtesy the artist/Stephen Friedman Gallery, London and New York/Jessica Silverman, San Francisco/Karma, New York; © Woody De Othello

Where is your studio?

The San Francisco Bay Area – my ceramic studio is in Richmond and I make paintings at home in Oakland. I used to paint in the ceramic studio, but that’s problematic because of the clay dust. There’ll be a thin layer gathering over it while it’s drying for a couple of days, so I realised that I needed to isolate those two different spaces.

How would you describe the atmosphere of where you work?

Those two spaces are very different. I make the paintings by myself, so I have more solitude in the painting studio (although me and my wife, who is a photographer, do share the space). But the ceramic studio is a full-blown production: I have three assistants who come and help me out. In the ceramic studio there’s a lot of communication – a lot of talking, navigating and teamwork.

The ceramic studio is in an industrial area in Richmond. There are a lot of welders and other makers who have warehouses around there – we share a wall with a woodshop, and they’re really noisy. There’s always background chatter and we’re normally playing music. It feels much more active, whereas the painting studio is a little bit more cerebral. Oftentimes I have headphones in while I’m painting, so it’s a much more closed-off space. I end up walking a lot – just walking up close then getting space and going back.

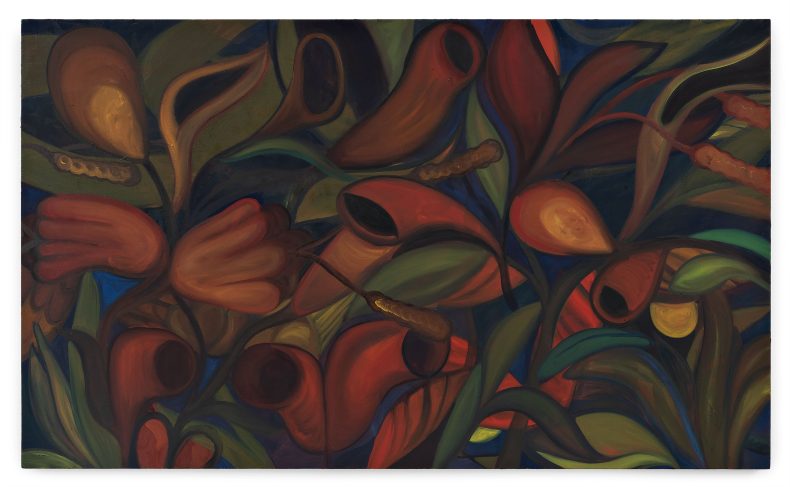

Fantasy under the Moonlight (2024), Woody De Othello. Photo: Phillip Maisel; courtesy the artist/Stephen Friedman Gallery, London and New York/Jessica Silverman, San Francisco/Karma, New York; © Woody De Othello

What do you like most – and least – about where you work?

Being in the Bay Area combines city life with proximity to nature in every direction, which is really nice. I think there’s something about the energy, the pace and the rhythm of the area that, for me at least, is conducive to being in your own bubble and making work. I also like spending time outside and that’s something that keeps me here.

The only thing I don’t like is that there’s no infrastructure for heating the ceramic studio, which is essentially just a warehouse without insulation. That’s a huge challenge in the winter as the environment really affects the clay. If it’s super cold, the clay doesn’t dry out, and if it’s super hot, the clay dries out real quick. Everything we make is slab built, made by constructing forms through hand-building. When you’re working with clay like that, there’s always this negotiation with environmental factors.

What do you listen to while you work?

If it’s me choosing music in the studio, it’s probably going to be either jazz or house music – it helps to power us through the working day. Painting is very different, though. Sometimes I listen to music, but most of the time it’s documentaries. While making the batch of work that just left the studio, I was listening to a series on the history of Africa. It’s good to be learning through an Afrocentric lens. I listen to the news and a lot of podcasts, too – it just depends on the day and the mood I’m in.

The Healers Gathered Around (2023), Woody De Othello. Photo: Phillip Maisel; courtesy the artist/Stephen Friedman Gallery, London and New York/Jessica Silverman, San Francisco/Karma, New York; © Woody De Othello

Do you have a specific studio routine?

I exercise then do computer work in the morning, so that when I go to the studio I don’t have to look at my phone or send emails and whatnot. I don’t work super late, either. I probably stop working around six or seven o’clock, sometimes even five. I like a nice consistent approach. Even if there’s nothing to do, which is rare, I’ll just go into the studio to sit there cleaning and organising. I like going in five or six days a week.

I’m a believer in being consistent, though when we’re nearing a deadline, I do have the capacity to push it. I’m recovering from a crazy push right now – I don’t think I took a single day off in January ahead of the Stephen Friedman show. There’s more than 30 artworks – paintings of various sizes, small pen drawings, a few freestanding ceramics with a base supporting a vessel, some smaller-scale tabletop ceramics: a big range of different forms and mediums.

What’s the most unusual object in your studio?

Every time people come here, they point out this bust I made in graduate school. It looks kind of demonic… the work I was making then was something else. My mom was super worried, like, ‘If this dude is making art, and this is what he’s making, I don’t know how it’s gonna play out for him!’. It’s now overseeing the studio from the top of a cabinet, like a guard or a kiln god. It has a dark pulse to it. There’s a little bit of grime, a little bit of attitude.

Great Soul (2023), Woody De Othello. Photo: Phillip Maisel; courtesy the artist/Stephen Friedman Gallery, London and New York/Jessica Silverman, San Francisco/Karma, New York; © Woody De Othello

What’s the most well-thumbed book?

That’s easy: Of Water and the Spirit by Malidoma Patrice Somé. I’ve bought like a dozen copies of this book to hand out to people. It’s been a guiding force for me. It’s about a man from Burkina Faso who is from a small tribe, the Dagara. He writes about his experiences growing up before he was taken away by French missionaries and spent a huge chunk of his life in the West. He finally escapes and goes on a voyage back home. He’s trying to get back into tribal life, but everybody in his community thinks there’s something wrong with him, so he goes through an initiation process. This book is about his journey, but for me it painted a picture of the differences between Western and indigenous ways of living. If anyone talks to me for more than an hour, I’m probably going to mention that book. I wouldn’t necessarily say that it has affected my artwork, but it is affecting the way that I live, in terms of trying to be more connected with nature and with showing up within a community. It’s a life ethos.

Who is your most frequent visitor?

Well, my wife and my team of studio assistants. I’m not able to make the work alone and I have three amazing hands-on assistants. Probably my dog, too. She’s always just like, ‘Dude, what the fuck are we doing here? Do you not see the weather out there?’ She has a threshold of a couple of hours. Gallery folks pop in and out, but that’s very infrequent. Sometimes I have friends come by, but the studio is very much about work.

I used to be kind of obsessive: I would take photos of work, and then go home and think about work. But now, though art is a huge part of my life, I’m also focusing on, like, how do I show up and spend time with the people around me? Not everybody wants to talk about artwork all the time.

Divine Support (2024), Woody De Othello. Photo: Phillip Maisel; courtesy the artist/Stephen Friedman Gallery, London and New York/Jessica Silverman, San Francisco/Karma, New York; © Woody De Othello

Who is the most interesting visitor you’ve ever had?

The first thought that comes to mind is my mom and my dad. I’m in California and they’re in Miami, so their trips here are very infrequent. The last time I had my folks here was June last year. It felt very special, very loving. Their lives are the reason why I have my life, you know, so I feel like me spending all this time making this stuff is just this weird, like, acknowledgement. That was very sincere and very sweet for me, though I guess my parents aren’t that ‘interesting’, really.

People who don’t have an arts background do always feel a little more genuine, because they give you a reaction without any art world knowledge. I always appreciate those reads more – like the one you’ll get from a delivery person, say. I have a buddy who is a musician, and when he comes by his feedback is all over the place, which is refreshing.

‘Woody De Othello: Faith Like A Rock’ is at Stephen Friedman Gallery in London from 8 March–13 April.