Städel Museum, Frankfurt

Assumption of the Virgin (c. 1650–55), Laurent de La Hyre

Laurent de La Hyre, who was born in Paris in 1606, was one of the chief exponents of Parisian Atticism, a mid 17th-century neoclassical movement also practiced by Jacques Stella, Eustache Le Sueur and several others. He rose to fame through several religious commissions and, in 1648, co-founded France’s Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture. His Assumption of the Virgin, a small, virtuosic oil painting that is thought to have been a preparatory sketch for a lost or unrealised altarpiece, has been acquired by the Städel in Frankfurt, a museum that has six drawings by La Hyre but, until now, no paintings. A busy, richly coloured work on the same subject by Guido Reni – one of La Hyre’s greatest inspirations – hangs in the same room.

Norton Simon Museum, Pasadena

Arabesque over the right leg, left arm in front (1880s), Edgar Degas

Edgar Degas was one of the great obsessions of Norton Simon, the industrialist and collector who gave his name to the museum formerly known as the Pasadena Art Museum in 1975. He acquired 69 master casts – the only set in the world cast directly from the French artist’s original wax and clay statuettes – in 1977, and the museum today holds one of the largest collections of Degas bronzes in the world. Arabesque over the right leg, left arm in front, modelled in the mid to late 1880s, is one of the few sculptures that Simon didn’t manage to buy in his lifetime; a bronze cast of the work, produced in 1919–22, has now been acquired by the museum and has gone on display alongside its companions.

Hepworth Wakefield

Sculpture with Colour (Oval Form) Pale Blue and Red (1943), Barbara Hepworth

The Hepworth made headlines this summer when it announced a public appeal to buy a sculpture by Barbara Hepworth that had been export barred by the UK government. Thanks to donations from almost 3,000 members of the public, on top of £1.89m from the National Lottery Heritage Fund and £750,000 from Art Fund, the museum has now secured the work for its collection. Sculpture with Colour (Oval Form) Pale Blue and Red was made in 1943, fairly early in the sculptor’s career, and is one of the first works still in circulation to use string. It is now on display alongside the artist’s ‘stringing map’, which was already in the museum’s collection.

Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid

Two early works by François Boucher

When Juan José Luna Fernández, head of 18th-century painting at the Prado, died in 2020, he left the museum a generous gift: his home in Madrid, which was subsequently auctioned for €3.2m. That money has gone towards several of the museum’s recent acquisitions, including these two early paintings by Boucher: The Birth of Adonis and The Death of Adonis (both 1723–25), the former depicting Adonis being born from a myrrh tree and the latter showing him slumped, mortally wounded and surrounded by putti. The only major Boucher work at the Prado is the gestural late painting Pan and Syrinx (1760–65); this acquisition allows visitors to get a sense of the arc of Boucher’s career while strengthening the museum’s holdings of rococo art.

Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford

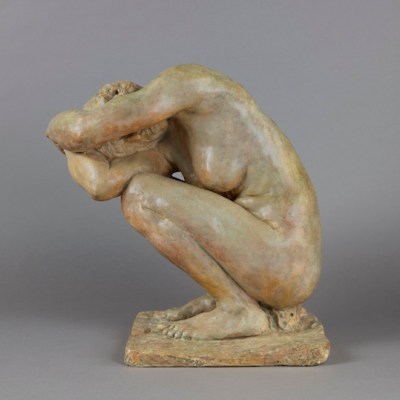

Study for the Head of the Implorer (c. 1894), Camille Claudel

Extant plaster casts of works by Camille Claudel are rare. This small plaster head, bought by the Wadsworth Atheneum at TEFAF earlier this year from Galerie Malaquais, is even more sought-after because it was never cast in bronze during the artist’s lifetime. The work is a study for the head of the ‘implorer’, the kneeling, pleading figure in what is perhaps Claudel’s most famous sculpture, The Mature Age – both an allegory of ageing and a comment on Auguste Rodin choosing his wife, Rose Beuret, over his lover, Claudel, in the 1890s. The original plaster cast of The Mature Age is thought to have been destroyed and only four bronze versions of the work remain, so this plaster provides a fascinating glimpse into how the supplicant evolved in shape and expression. It is the first Claudel work to enter the Wadsworth’s collection.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

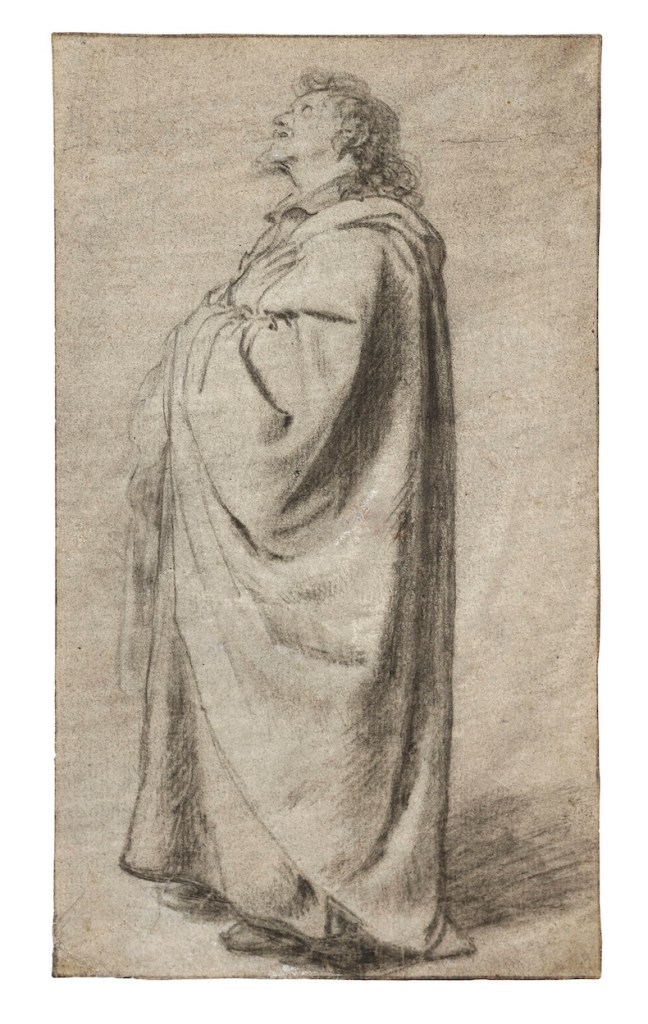

Saint John the evangelist (c. 1629), Jan Lievens

Jan Lievens has long been overshadowed by his contemporary Rembrandt, but in the 17th century the artists were close, both personally and in terms of style. They appeared as models in each other’s paintings and may even have shared a studio in Leiden in the 1620s; their style of portrait painting, character studies and genre scenes, heavily influenced by the Utrecht Caravaggisti, became so similar that their peers, it is said, struggled to tell their work apart. This small drawing, a mournful depiction of Saint John the Evangelist that the Rijksmuseum has acquired from Sabrier & Paunet, was produced during that time of close friendship with Rembrandt. Drawn in black and white chalk, it shows the artist’s supreme skill at handling line and shade.

Huguenot Museum, Rochester

His Master’s Voice (1937, after Francis Barraud)

In 1898 the Huguenot artist Francis Barraud painted an unremarkable picture of his dog, Nipper, shown listening to a cylinder phonograph. Barraud offered the work to Edison Bell, the company who had manufactured the phonograph in question, but was rejected – apparently with the remark, ‘Dogs don’t listen to phonographs’. Undeterred, he took the painting to the newly founded Gramophone Company, who agreed to buy the picture if Barraud replaced the phonograph with one of their own gold-horned Gramophones. The image, known as ‘His Master’s Voice’, became one of the most well-known trademarks of the 20th century – a version of it is still on HMV’s logo – and Barraud spent the rest of his career producing copies of the work. A faithful copy of the work made after Barraud’s death has now been acquired by the Huguenot Museum in Rochester, where an unveiling ceremony was attended by Barraud’s descendants.