Drawn from the Bodleian’s vast collections, this exhibitions features maps from ancient, premodern and contemporary cultures across the globe, as well as fictional maps by figures such as C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien, to explore what maps can tell us both about the places they depict and the people who made them. New commissions by contemporary artists are also on display, while the exhibition concludes with a look at cutting-edge developments in mapmaking. Find out more from the Bodleian Library’s website.

Preview the exhibition below | View Apollo’s Art Diary here

Map of the world (1154), al-Sharif al–Idrisi. Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford

Al-Sharif al-Idrisi’s map of the world was published in 1154, in the Arab scholar’s Entertainment for He who Longs to Travel the World. Commissioned to create the book by King Roger II of Sicily, al-Idrisi drew on a vast range of Greek, Islamic and Christian sources to create one of the most comprehensive geographical texts of the medieval world. The map is oriented with the south at the top; depicted on the otherwise bare and unknown African continent are the mountains from which the Nile was thought to spring.

A Pacific stick chart (1896), Marshall Islands. Photo: © Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford

These remarkable stick charts map out the swells and currents of the oceans between Pacific islands many thousands of miles apart, signified here by cowrie shells. Navigators from the Marshall islands would memorise the patterns before embarking on their voyages.

The Gough map of Great Britain (late 14th century). Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford

The Gough map, named after the antiquarian Richard Gough who bequeathed the map to the Bodleian in 1809, is the earliest recognisable depiction of the island of Great Britain. Dating from the late 14th century, it is oriented with east at the top.

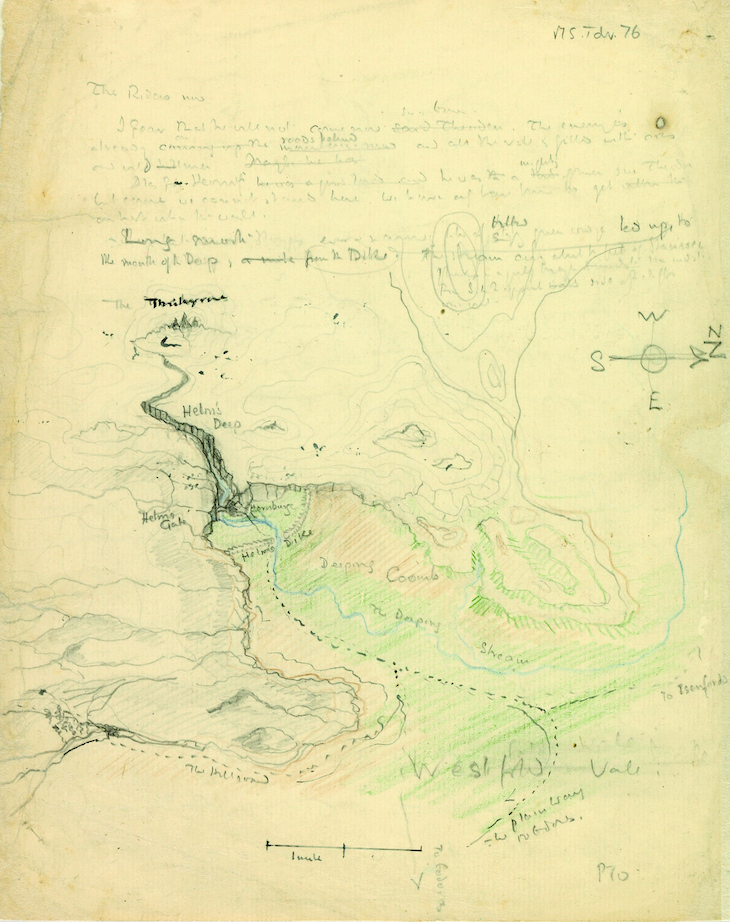

Map of Helm’s Deep valley and the Hornburg fortress (1942), J.R.R. Tolkien. © The Tolkien Estate Ltd 1976, 2015

In 1942, perhaps bored while marking, Tolkien sketched on a student’s exam paper this map of Helm’s Deep valley and the Hornburg fortress, the site of a major battle the second volume of The Lord of the Rings. Such fantastical cartography was, for Tolkien, a way of plotting out the events of his stories; he spoke of the need to ‘first make a map and make the narrative agree’.

Map of Nowhere (2008), Grayson Perry. Courtesy the artist, Paragon/Contemporary Editions Ltd and Victoria Miro, London/Venice; © Grayson Perry

The artist Grayson Perry frequently manipulates the form of maps to reflect his impressions of contemporary society. This work plays on the circular form of medieval mappae mundi (such as al-Idrisi’s above), while positioning the artist himself as Christ, at the centre of the world, satirising the contemporary obsession with selfhood.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](https://apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Sitting pretty – the world’s best museum benches