Charles Avery is telling me about the zoo in Onomatopoeia, the capital city of the fictional Island he has been describing in captivating drawings, sculptures, texts, furniture and film for roughly 11 years.

‘A lot of people who come to the Island come in search of the Noumenon, this yeti-like being which represents the Ultimate Truth, and no-one has ever [caught it]. It’s almost like the Islanders wanted to create a place for the Noumenon to be,’ he explains. The zoo is depicted in two drawings currently on view at Pilar Corrias gallery in London: the larger one maps the inner circle, while the other provides an aerial view of a swimming pool atop the precinct’s central tower, which, I am told, is connected by means of a narrow pipe to an aquarium containing a sea creature. ‘The Islanders like to be in the same body of water as this being they keep in there, for the frisson that they get from swimming [near it],’ he explains.

Installation view, ‘Charles Avery, The People and Things of Onomatopeia: Part 2’ at Pilar Corrias gallery, London. Courtesy the artist and Pilar Corrias Gallery, London. Photo: Damian Griffiths

Avery’s knowledge of the Island is sprawling: within five minutes of meeting, a day before the show’s opening, our conversation has spiralled into a dissection of the inhabitants’ abhorrence of the square, their rejection of absolute time, and their opportunistic approach to day-to-day life. But he stresses his knowledge is not unequivocal, and much remains unknown. ‘When I don’t know things, I just leave them blank,’ he says, referring to a vague cage structure in the larger of the two zoo pieces. ‘I don’t try to answer things I don’t know.’

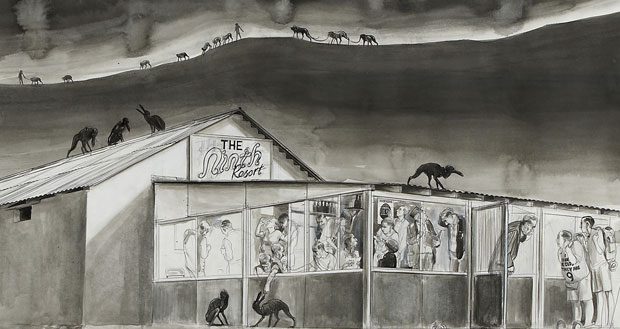

Now is a good time for Londoners to explore Avery’s Island: a study of the project is also on view at the David Roberts Art Foundation, filling several rooms and centring on a large drawing of a dock scene from the David Roberts Collection. The show begins with a small, atmospheric watercolour showing the Hunter — an explorer-protagonist from Triangland, a colonial superpower analogous to the ‘real’ world — alighting on the Island. As with the show at Pilar Corrias, there are drawings, sculptures, pieces of furniture, wallpaper, and posters, but also a room providing a snapshot of the artist’s studio practice, including sketches, objects and photographs. A view of the Scottish island of Mull, where he grew up and spends much of his time, is a reminder of its centrality to his work.

Materials and documents from the artist’s studio on display in ‘Study #15. Untitled (The Ninth Resort), Charles Avery’ at DRAF, 2017. Courtesy the artist and DRAF. Photo: Tim Bowditch

Critic and curator Nicolas Bourriaud once wrote that the project’s ambition is ‘to discover bit by bit, an unknown territory while simultaneously inventing it.’ Everything that constitutes the work has its genesis in periods of what Avery calls ‘abstract reverie’, but the invention isn’t merely fanciful, or gratuitous. Logic is followed, the structure adhered to. In all of the drawings are areas of striking detail, but frequently also unmapped zones and wraithlike characters waiting, perhaps, to be filled out. ‘The Island has become more of a place that helps me to think, it’s become an instrument for my thinking and inspiration for the work that I make,’ says Avery.

Different philosophical and mathematical ideas are playfully explored through the geography of the Island, its flora and fauna, as well as the cultural idiosyncrasies of its inhabitants. Transposing Immanuel Kant’s concept of the noumenon, or that which is unknowable through the senses, to a beast whose existence is fiercely debated by the Islanders, is one especially delightful example.

Untitled (The Ninth Resort) (detail; 2010), Charles Avery. Courtesy the artist and David Roberts Collection, London

‘When I first started the project, I thought a bit naively that I would create a map that defined the territory and then I would fill it in and I’d just describe the flora and fauna and topography etc. and just proceed,’ he says, with a laugh. After grappling with the nature of the structure, and worrying it might become overbearing, he came to realise ‘that actually the island and Triangland represent all the great dualities; it represents the subject and the object and it represents the real and the unreal, it represents inside the gallery and outside the gallery, if you like. So all these dualities – you can understand them through the project.’

If the drawings function as reportage of the island, Avery’s sculptures and posters are ‘relics’ of the place, with certain items seeming to be taken directly from the drawings. A discarded shoe, which features in a large drawing of Onomatopoeia’s Place de la Révolution on view at DRAF, appears in three-dimensional form on a table in another room of the same show; a rope coiled on top of a crate has its referent in another work on paper, also on view.

A symbiotic relationship exists between these items and the drawings, just as it does between the artworks and the overarching conceptual framework of the Island. This relationship extends further, linking specific works in the different London shows: a drawing of two bikini-clad girls leaning over a balustrade at DRAF, for example, is taken from one of the zoo drawings at Pilar Corrias. The former is one of several portraits of the Islanders culled and enhanced from larger works, which the artist variously refers to as ‘little jewels’ and ‘distilled droplets’. There’s a tenderness to the drawings, a special attentiveness to gesture and dress, and I’m not surprised to learn that Avery loves to draw the Islanders. ‘The people are such an important part of it and it kind of emancipated them from their situation, from the situation of the Island, from the situation of this arch narrative, this epic system, and then you could just enjoy them as people,’ he says.

Untitled (Two Girls on Balcony) (2016), Charles Avery. Courtesy the artist and Pilar Corrias, London. Photo: Tim Bowditch

This labour of thought and invention is, understandably, as difficult to cohere as it is fascinating to behold. ‘I’ve been working on it for 11 or 12 years now. What I thought it was in the beginning, and where I think I am with it now, and what I think it means are just so wildly different,’ Avery says. ‘It’s something I’m struggling with, it’s like an epic novel I’m attempting to bring together. I’m grappling with more and more assets and deciding what’s relevant, deciding what the Island itself represents. I’m a lot closer now, I feel I’m in a lot better shape now than I was seven or eight years ago, but it’s still a struggle.’ A set of bookends, each bearing a model of a one-armed snake, appears in both shows. The set at DRAF contains three books about the project; the pair at Pilar Corrias are placed on an obround table, with a few of feet empty space separating them. Avery imagines a long-gestating encyclopaedia of the island one day residing there. ‘However far apart they are represents how I’m feeling about the project,’ he says.

‘Charles Avery, The People and Things of Onomatopeia: Part 2’ is at Pilar Corrias, London, until 17 February. ‘Study #15. Untitled (The Ninth Resort), Charles Avery’ is at the David Roberts Art Foundation until 8 April.