Frieze’s arrival in Seoul for its first fair in Asia has certainly caused some excitement. It is not every edition where the mayor turns up at the opening surrounded by a bank of photographers. Jason Haam, a young Korean gallerist who specialises in showing non-Korean artists at his gallery in Seongbuk – known as the Beverly Hills of Korea with its winding, hilly streets – and is showing at Frieze, described the presence of the fair as ‘like the Olympics happening in Korea, I just want to be part of it’. There is no doubt that the queues that snaked around the entrance to the fair, which took place not in one of Frieze’s trademark tents but in the vast and less personal Coex convention centre, looked more like something one would find at a sporting event than an art fair. What happened at this convention centre has the potential to have a more lasting effect than anything that takes place on a sports field.

The art market has long been in thrall to the money and activity in Asia, by which galleries and especially auction houses mean China. An event of international prestige such as Frieze has the potential to establish a new centre of dealings for the art world, as well as being seen as the culmination of a movement that began with international galleries such as Pace, Thaddaeus Ropac and Perrotin opening in the city. James Lee from BB&M, which started as a consultancy and now operates as a gallery in the capital, described the arrival of what he calls these ‘blue chip galleries’ as ‘salutory’. While this augurs well, the question is whether this would add up to a success for both Seoul and Frieze.

Photo: Let’s Studio; courtesy Frieze and Let’s Studio

The current Covid regulations and the political situation in Hong Kong have not made it accessible as a centre for the art world. Collector Rajeeb Samdani, who founded the Samdani art foundation with his wife Nadia, said, ‘I love Hong Kong but with the current situation and challenges, I’m not sure when they are going to open up or what is going to happen, so I had to come [to Seoul].’

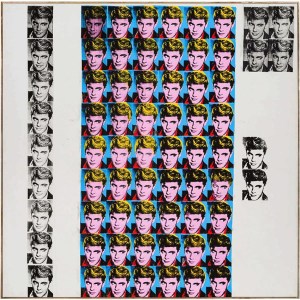

Troy (1962), Andy Warhol. © 2022 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The fair itself did not look that dramatically different from other editions of Frieze or Frieze Masters. Typical art-fair art was hanging on booths and most of the galleries had put the effort into offering works in the top of their class, even if Katherine Bernhardt seemed to crop up more often than most. Most notable was Acquavella who had curated an astonishing group of works in the Frieze Masters section. At the centre of their stand was Andy Warhol’s vast Troy, while they also showed an atypical but very striking Basquiat Bird alongside Picasso’s Femme au béret rouge à pompon and Mondrian’s Composition: No II, with yellow, red and blue. Richard Nagy performed the same trick he pulled off in Art Basel in 2019 with a selection of extraordinary works by Egon Schiele transforming his stand into something of a calling card for a collector base that might not be well acquainted with works of early Austrian Expressionism.

Unusually, three of the 18 stands in the Masters section were selling manuscripts and books. Daniel Crouch, owner of Daniel Crouch Rare Books, pointed out that ‘We’re map dealers so by definition we are global.’ His arrival in Seoul wasn’t out of the blue: ‘I’ve been doing business [in Korea] with institutions and one or two private collectors for about 18 years,’ he says. ‘You need to remember, printing was invented in Korea, they regard the very slow progress of printing in Europe as something that amuses them.’ This points to a sophisticated, well-established collector base in Korea that goes some way to explaining what Crouch describes as an ‘extraordinarily busy’ day.

Dr. Jorn Gunther Rare Books at Frieze Seoul 2022. Photo: Let’s Studio; courtesy Frieze and Let’s Studio

Further evidence of this collector base comes from Thaddaeus Ropac, who opened a gallery in Seoul a year ago. ‘You have great academies, which produce great artists, you have curatorial teams on an amazing level, and it’s the place with the biggest number of private museums in the world,’ says the gallerist. Of course, what he is describing is a local collector base rather than a continent-wide situation. Yet in a country that is one of the largest economies in the world this is not to be sniffed at. Especially when there are so many wealthy young people. Notable in the fair was the excitement around actors from Squid Game and also, of course, the obligatory arrival of RM, the rapper from K-Pop sensation BTS. Ropac sees a connection between these cultural figures – RM is vocal about his support of the arts and BTS have included promoting visual art and exhibitions as part of their activities – and young collectors: ‘There’s a young generation of collectors and K-Pop was very influential to this,’ he says. ‘The collectors are much younger and they are educated and this is what is so interesting.’

What this points to is a fair that performs strongly in a local environment which isn’t quite the gateway to an international Asian audience that some galleries might have hoped for. Brett Gorvy, one of the founders of LGDR asks the question, ‘If Hong Kong and mainland China have been problematic, where do you find access to a strong Asian audience?’ which has led to a lot of expectation and anticipation. He has taken a ‘more measured’ view seeing this as part of the building block of an Asian strategy. There are local idiosyncrasies to any fair and there seems to be a particular flavour to Seoul. ‘Most fairs are over after the first day if you’re lucky maybe the second day. By the second day of Basel in Switzerland anyone of significance has left. The sense [in Seoul] is that every day, we’ll have a different flow of people and people will come back,’ says Gorvy. As a result, LGDR have taken the unusual step of preparing different hangs for their booth for each day of the fair to express the different sides of their gallery. Day one proved hugely successful with a booth dedicated to works by Joel Mesler and his LA Korea Town-inspired paintings that translated well to a Korean setting. Fontana and Soulages will at least announce another direction for the gallery.

Dastan gallery in the Focus section.Photo: Let’s Studio; courtesy Frieze and Let’s Studio.

Talking to Hormoz Hematian, director of Dastan, an Iranian gallery that is part of the Focus section of the fair, something else became clear. He is showing the works of Ali Beheshti. These black-and-white ink works that render the motifs of carpets as 3D figures have a still beauty about them, using a technique that connects to a tradition that stretches across the continent such as Chinese ink drawings. ‘Iran is not the first place that pops into mind when people hear “Asia”, but it very much is a part of Asian culture,’ says Hematian. While Frieze is successfully bringing a new audience to many of the galleries who are taking part and providing a new energy to the local gallery scene it is very much Korean. This is not a failure to reach Covid-struck countries but a sign that the word ‘Asian’ in relation to the art market is becoming less and less meaningful. It is not so much that there is one Asian market any more: there are a variety of markets across the continent and anyone with global ambitions is going to have to work out how best to approach them.

Frieze Seoul is at Coex, Seoul until 5 September.