In 2001, Homan Potterton enjoyed unexpected literary success with a childhood memoir, Rathcormick – unexpected because hitherto he had been known as an art historian and former director of the National Gallery of Ireland. But for those aware of him only in these guises, the book provided an insight into the author’s origins as the youngest child of prosperous Irish farming stock. Potterton might have followed the example of his forebears and stayed in rural Ireland, but at the age of 16 he visited France, was taken to a series of chateaux and then guided by a distant cousin around the Louvre. Returning home, he realised that he was not, as had previously appeared to be the case, a fish out of water, but ‘had merely been swimming in the wrong pond’.

Having studied history of art at Trinity College, Dublin, he undertook postgraduate research at Edinburgh (he had been spurned by Anthony Blunt at the Courtauld Institute), which in 1975 led to his first book, a guide to Irish church monuments. Then, after briefly working for the Irish Georgian Society, he secured a position at the National Gallery of Ireland, going on in 1974 to become an assistant keeper at the National Gallery in London (under then-director Michael Levey). There, as he later wrote, he had ‘the time of my life’; among other activities, he curated a highly successful exhibition of 17th-century Venetian painting (and wrote the accompanying publication), as well as producing a best-selling guide to the institution.

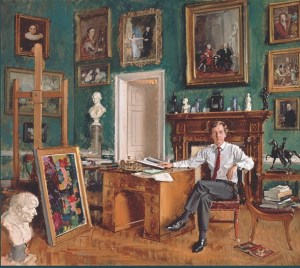

Portrait of Homan Potterton in the Director’s Office of the National Gallery of Ireland (1986), Andrew Festing. Courtesy Merrion Press

Potterton was disciplined, hard-working and ambitious. In 1979, at the age of 33, he returned to Dublin to become the youngest-ever director of the National Gallery of Ireland. As in London, he proved to be energetic and enterprising, not least by producing the first comprehensive catalogue of the gallery’s collection. Although his area of expertise was Old Masters, he added more recent works to the NGI’s holdings through the acquisition of pictures by the likes of van Dongen, Nolde and Soutine, while the Máire MacNeill Sweeney Bequest meant the collection came to include paintings by Gris and Picasso. Most importantly of all, he was instrumental in persuading Sir Alfred and Lady Beit to donate their own outstanding collection to the gallery, first displayed on the premises in 1988 in an exhibition modestly titled ‘Recent Acquisitions’.

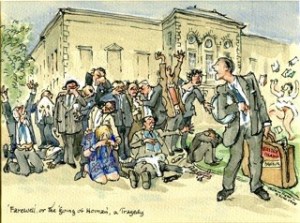

To widespread surprise and consternation, he then announced his resignation. In a second volume of memoirs, Who Do I think I Am? (2017), he explained the reasons behind this decision. The Irish civil service, with which he had to deal, does not care for speed and chose to play the tortoise to Potterton’s hare: several more decades would be allowed to pass, for example, before the NGI received the refurbishment for which he had clamoured. In addition, he had to engage with an interfering Taoiseach (prime minister), Charles Haughey, who liked to imagine himself as a latter-day Medici. In truth, he was a vulgar blaggard: as Potterton told listeners to Irish radio a few years ago, Haughey wouldn’t have known a Titian from a turnip, but that didn’t stop him persistently meddling in the gallery’s affairs.

Farewell, or the Going of Homan, a Tragedy (1988), Thomas Ryan. Courtesy Merrion Press

Following Potterton’s departure from the NGI, one might have expected him to take up a position elsewhere, but this was not the case: in fact, he never held another full-time job. ‘I was burnt out,’ he wrote of the end of his time in Dublin. But perhaps he was also disillusioned with the art world and officialdom because although he continued for some years to write, not least for Apollo, and also acted as a highly skilled editor of the Irish Arts Review, by the start of the new century he had largely left that world behind. More recently, his attention became focused on his own family’s history and on the vanishing culture of Protestant Ireland, the theme of a novel, Knockfane, on which he worked for many years – I have an early version he sent me for comment almost a decade ago – and which eventually appeared in print last year.

Homan Potterton never publicly expressed regret for his early exit from the art world, but in the aftermath of his death from cancer at the age of 74, one cannot but wonder what else might he have done if only his time as director of the NGI had been happier. For all that he unquestionably achieved, what fresh paths might his career have followed under other circumstances? Alas, now we shall never know.