Art crime is never far from the headlines. Recent months, for example, have seen ongoing coverage of the Yves Bouvier affair, fakes at New York’s Knoedler Gallery, and the risk of antiquities looted from the Middle East hitting the Western market where the proceeds of sale might be used to fund terrorism, or that profits might be made on fake looted antiquities. This blend of subject matter based around important cultural objects, illicit activity and, crucially, money, seems to hold much of the press and public in thrall. Publications such as Riah Pryor’s Crime and the Art Market, and Art Crime and Its Prevention (a handbook also recently published by Lund Humphries), which investigate the links between art and crime are more than likely to coincide with news stories that make them appear particularly timely.

In Crime and the Art Market Pryor attempts to describe the roles of the various players within the art market, and the criminal activity linked to or within it – and largely succeeds in doing so. Pryor’s background as a researcher for the Art and Antiques Unit at the Metropolitan Police, and also as a journalist for, among others, The Art Newspaper, is telling. The clarity with which she examines the links between the diverse actors and the networks they form is immediately apparent, and her past proximity to the fight against art crime shows in the way she carefully avoids glamourising art thefts.

To outsiders, the art market can appear as impenetrable as the most complex of financial markets, and without any apparent coherent oversight or regulation. Pryor is aware that outlining the roles that various parties play is vital to understanding how their actions encourage, permit, hinder, or fight crime associated with the market.

As a practitioner in the field, it is gratifying to see Pryor insist that accurate art crime statistics are few and far between. In particular, she debunks the recurring claims that art theft is responsible for losses of $6 billion per annum, or that art crime is one of the world’s most lucrative and common forms of illicit trafficking. The frequency of such claims and the loose or exaggerated way in which data is bandied about often undermines legitimate criticism of aspects of the market. A recent example is a remark made by John Phillips, the US Ambassador to Italy, in a speech last year: ‘INTERPOL estimates that the illicit trading in cultural property produces more than $9 billion in profits each year – only human trafficking, narcotics and weapons trades generate more illicit revenue.’ Here are two statements for which there is no supporting evidence. Recognition of the damage that such comments can cause demonstrates that Pryor is well equipped to tackle the challenge of reassessing the nature of crime within the art market.

As a practitioner in the field, it is gratifying to see Pryor insist that accurate art crime statistics are few and far between. In particular, she debunks the recurring claims that art theft is responsible for losses of $6 billion per annum, or that art crime is one of the world’s most lucrative and common forms of illicit trafficking. The frequency of such claims and the loose or exaggerated way in which data is bandied about often undermines legitimate criticism of aspects of the market. A recent example is a remark made by John Phillips, the US Ambassador to Italy, in a speech last year: ‘INTERPOL estimates that the illicit trading in cultural property produces more than $9 billion in profits each year – only human trafficking, narcotics and weapons trades generate more illicit revenue.’ Here are two statements for which there is no supporting evidence. Recognition of the damage that such comments can cause demonstrates that Pryor is well equipped to tackle the challenge of reassessing the nature of crime within the art market.

If there is a gap in the wide range of market forces covered in the book it is perhaps in relation to art insurance. The growing potential of the financial services industry to bring further improvements to the operation of the art market is well covered here, be it through increased self-regulation or the imposition of legislation. Yet little is said of the possibility for significant changes to be brought about through insurers’ direct involvement with the trade, if they were to act across the market. This might include insisting on some proof of title and provenance before offering insurance cover: after all, if the artwork is stolen, the insurer might claim title to it one day if found. There are rare occasions when a claim is paid out and, if the item is later located, for restitution claims to emerge, or doubts as to authenticity.

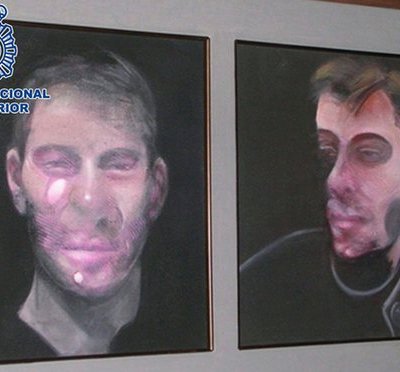

There are areas where Pryor’s commentary omits aspects that might be more apparent to someone working closely within the art market, for example in making clear how much more difficult it can be to tackle the problem of fakes and forgeries than stolen or looted art. When the latter is identified there is almost always someone to whom this is good news, a victim or an insurer perhaps; the same can rarely be said of the discovery of fakes or forgeries, in which all financially involved parties usually stand to lose out, and where proof of authenticity may hinge on a difference of opinion. Similarly, while Pryor rightly states that it is too early to measure the full impact on art crime of what she terms ‘today’s digital revolution’, it is nonetheless the case that the evolutionary effects of technology on art crime can already be seen in some areas. It is now possible to target the transport of artworks by hacking into email accounts and changing the destination address for shipping so that an item is delivered to an alternative, often empty address where a fraudster takes delivery and then disappears. Until the rightful recipient complains that nothing has arrived, no one is aware of the crime.

Yet journalistic brevity and the pacing of Pryor’s book far outweigh the occasional omissions that they lead to; it is accurate and informative. Even when writing about complex issues like the interplay of different legal jurisdictions on claims for stolen art, something that lawyers can cover in painful detail, Pryor manages to convey the relevant points without becoming caught up in unnecessary details that might confuse most readers.

As an up-to-date introduction, Crime in the Art Market should appeal to anyone with an interest in the topic. One can only hope that all journalists tempted to write about art crime will read it before they think too hard about attention-grabbing headlines. It is time that crime in the art market was taken as seriously as any other kind of crime. Pryor’s text is a good starting point.

Crime and the Art Market by Riah Pryor is published by Lund Humphries (£30).

From the October issue of Apollo: preview and subscribe here.