From the November 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

The art of collecting and the world of auctions meet frequently; when they do, it usually means big money for both the sellers and the auction houses. This November, what could be the most valuable collection ever comes to auction, as Christie’s offers the works assembled by Paul Allen, co-founder of Microsoft. The expectation is that this could be the collection that breaks the billion-dollar barrier, setting a new world record. But as Laura Paulson, the chief operating officer of Gagosian Art Advisory, says, ‘Records get broken every five minutes.’

Paulson knows a thing or two about records, having worked on the auction of the Macklowe Collection, which sold 65 works for more than $922m earlier this year, setting the current record. Paulson was adviser to Linda Macklowe, who saw the promise of Jeff Koons long before almost anyone else, while at the same time appreciating the bold brushwork of de Kooning. Before she was working in this way, behind the scenes, Paulson was global chairman of 20th-century art at Christie’s. Epithets like ‘rainmaker’ are frequently bandied about when people talk about this time in her career. She was part of the apparently unstoppable trio, alongside Brett Gorvy and Amy Cappellazzo, that drove the results of a single evening auction to a now paltry-looking $691m in 2013 – a watershed moment for the market, which made the billion-dollar sale week seem achievable. Still, Paulson says, ‘I don’t really think about the value.’

Paulson has set herself apart from her former Christie’s colleagues by specialising in and relishing the challenge of understanding collections and how collectors work. She brought to sale collections such as David Pincus’s and, most famously, the collection of Victor and Sally Ganz. She is not afraid of making money: ‘You want things to do well,’ she says. ‘You want there to be upside, you want “happy” on both sides, and a happy buyer and a great result reflects the quality of the work.’ So there is often much more to the work Paulson does than pumping up the yield of an artwork.

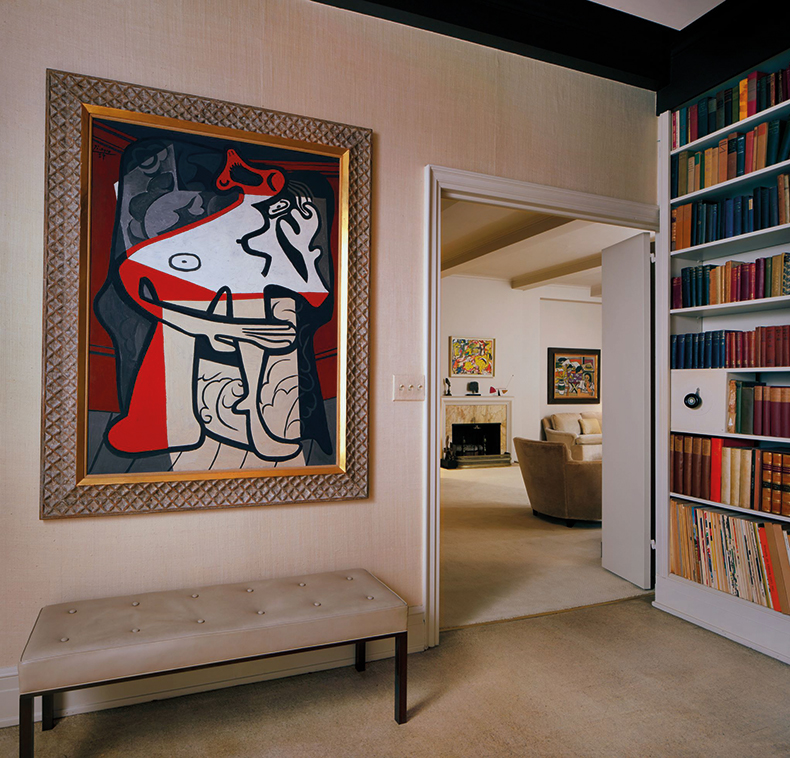

Pablo Picasso’s Femme dans un fauteuil (1942) in the house of David Solinger, whose collection will be on sale at Sotheby’s in November. Photo: Sotheby’s; © Succession Picasso/DACS 2022

Paulson began her career in the 1980s at McKee Gallery, on the fifth floor of the Fuller building on 57th Street and Madison Avenue. It was a small gallery with only David and Renee McKee, the gallery’s preparator and Paulson, who was ‘always ready to help’. She describes the building as the ‘nerve-centre mecca for galleries’ at that time.

It came with the bonus of being above A&M records; ‘You had Miles Davis and Bob Dylan wandering into the galleries,’ she says. The more important side of Paulson’s work there was not the celebrity musicians, but the collectors who were beginning to assemble works of art. She would see ‘all the major collectors making their treks on Saturdays or the major groups of collectors from the West Coast or Chicago all come through’. It was a place where major collectors not only began to shape their interests but galleries such as André Emmerich, Charles Egan, Zabriskie and Pierre Matisse were all under the same roof; camaraderie between the galleries grew in a way that probably wouldn’t happen today. Paulson remembers David McKee taking a collector ‘down the street to Blum Helman to show him something great that they had’. For Paulson, ‘it was the first exposure to the kind of passion and excitement that collectors worldwide were really beginning to develop […] It was a generation coming of age, from the 1960s to the ’80s.’

It was, in many ways, a different way of collecting from how people operate now. ‘It wasn’t as if everyone at that time was dealing with the amount of [money]. They weren’t hedge-fund billionaires, they made very astute acquisitions, but they made them thoughtfully and they also often had to wait – they would pay over time,’ Paulson says. This stands in contrast to the people building their collections by spending big at auctions, like Liu Yiqian, who in 2015 bought a Modigliani nude at auction for $170.4m to be the crowning jewel in the Long Museum in Shanghai, changing the museum’s reputation overnight.

‘Of course, everyone would have their own programmes,’ Paulson says, ‘but there was an interesting community and I think there was trust at the local museums. [The collectors] worked with their local institutions, and often the curators and directors there would give them an insight.’ The idea of collectors building their knowledge through local museum curators and through studying and discussing artists’ work, conjures an attitude that feels slightly quaint in the quick Instagram world, where art buyers spot a work and pursue it immediately. Necessarily, this changes the way collectors understand what they are putting together. ‘It was built on a practical but very passionate way [of working]; people had to work hard to collect,’ Paulson says, ‘They had to make their decisions carefully, whether it was a great drip Pollock or a beautiful Clyfford Still or a Guston. It was a very judicious decision but something they really wanted, and they worked to have it.’

Paulson is ‘quick to not dismiss’ the way collections are more typically put together today. ‘The market has become so global and people do have varied approaches,’ she says. This more often involves advisers, rather than curators. Predictably, the effect of this can be seen in the collections themselves, ‘Sometimes I don’t see the level of nuance in collections that I would see in the past,’ Paulson says. Yet the depth and quality of a good collection still resonates today. Paulson mentions the Richard E. Lang and Jane Lang Davis collection that sold at Sotheby’s in 2019, a collection of 20th-century art including works by Franz Kline, Giacometti and Calder. This collection of what Paulson calls ‘great material’ that she helped bring to auction ‘still has an appeal to both the younger and older generation. You know that urge for the quality is still meaningful.’

Working at this level also meant that collections could have a more interesting approach. ‘It wasn’t just about the trophy picture everywhere or [that the collectors’ taste] had to be validated in some way, [they] also had the courage to buy great drawings by artists or younger artists that they’d seen,’ Paulson says, ‘and not everything found its way into the world of art history or the market, but it was that kind of interest and trust and passion that made the question [of what to collect] so interesting.’ Indeed, a large part of this was facilitated by the fact that collectors were pursuing their own passion and so free to pursue works that Paulson describes as being ‘outside of their level of comfort – but they believed in something or someone enough to acquire something, so there are obviously surprises.’

Brice Marden’s Elements IV hangs behind Jeff Koons’s Aqualung from the Macklowe collection in preparation for auction at Sotheby’s. Photo: Sotheby’s; © ARS, NY and DACS, London 2022; © Jeff Koons

When a collection is successful it becomes more than the sum of its parts, it goes beyond just the quality of an individual work. For Paulson, it is about the personality of the collector. ‘It’s really one of the one of the most interesting things, because it really is a Rorschach of a couple, a person, or a way of life, and how the works were chosen, the aesthetic. It is a very hard thing to define but it is so clear,’ she says. ‘I look back to all the various catalogues, from [Lindy and Edwin] Bergman to Robert Shapazian, Max Palevsky, it’s just so wonderful to see how whatever drove every one of these individuals to bring art in to their life, that pursuit, is just so unique to their sensibilities and their wiring.’ These three collections that Paulson picks out are all very different: the Bergman collection was focused on the works of Joseph Cornell and grew to become a glimpse of a particular attitude to Surrealism; Robert Shapazian doggedly pursued some of the finest works of Marcel Duchamp before widening his net to include artworks that had some relationship to Duchamp’s themes, such as Andy Warhol’s A Set of Boxes (1964); Max Palevsky’s collection stretched from antiquities to Frank Stella. It is their development that makes these collections seem alive and interesting. ‘For someone like Max Palevsky, who died back in 2010,’ Paulson says, ‘it was all about red, yellow, blue. It started with Léger, it went to [Richard] Lindner and then went to Lichtenstein, and then he steamrolled the whole thing into Judd – you watched the figuration melt into abstraction[…] It was just very profound.’

The sides of the collections that don’t make it to market seem to be the aspect that most excites Paulson. ‘What I find so interesting is the correspondence, the ephemera around the collection,’ she says. ‘The day-to-day correspondence shows the authenticity of the people, their collecting and the range of which art was a part of their lives.’ It is hard to deny the interest of letters from Joseph Cornell to Edwin Bergman, or from Alexander Calder, working on a ‘McGovern for President’ poster with Lindy Bergman, and these examples do indeed suggest a relationship between artist and collector, a depth of engagement all too often lacking in the contemporary art world today. Where now would one find an exchange between collector and artist such as the telegrams David Solinger sent to Willem de Kooning? Paulson remembers reading them as she prepared for the Solinger sale at Sotheby’s New York, scheduled for 14 November: ‘David kept everything. I’ve gone through sheets and sheets of paper – everything chronological and copied, you know, xeroxed and carbon-copied, and it’s just extraordinary; the handwritten letters from artists to him, just asking about pricing and getting this done, but what you see is how it all works.’ This includes ‘several telegrams that he sent to de Kooning – “I’m coming down [to the studio] at five o’clock” – I don’t think de Kooning had a telephone in his studio.’

Paulson’s enthusiasm for the minutiae of collecting, the hard work and details of personal interaction and her ability to place it in a historical context perhaps explains why she has a reputation for bringing seriousness to the appreciation and understanding of the collections with which she works. When she worked with Sotheby’s on the Macklowe collection, she felt her role was ‘to ensure that this collection was presented at the highest level of scholarship and beauty’. The Macklowe sale came out of one of the most acrimonious divorces New York has seen, via a court order forcing a couple who could not agree on the division of the collection to sell it. That was, as Paulson says, ‘an event that wasn’t necessarily a happy event for some of the people involved, but regardless, it had to reflect the quality of the collection and the rigour and compassion and time that had been devoted to collecting works.’ The real art of collecting goes beyond the purchase. It is, as Paulson is only too aware, a way of life. As she says, ‘It’s not just a picture on the wall, it represents something more.’

From the November 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.