A round-up of the week’s reviews and previews

‘Earth Martyr’, ‘Air Martyr’, ‘Fire Martyr’ and ‘Water Martyr’ (all 2014), Bill Viola Courtesy Auckland Castle Trust. Photo: Mark Pinder

Auckland Castle’s plan to revive religious art (Emma Crichton-Miller)

Religious art is deeply unfashionable. It refuses irony, the primary tool contemporary art, and it discomfits by challenging the boisterous secularism of much contemporary life. The religious art of the past we can comfortably package – its historical cultural frameworks can be appreciated but do not have to be entered into – but contemporary religious art forces questions about creed and belief we often prefer to avoid.

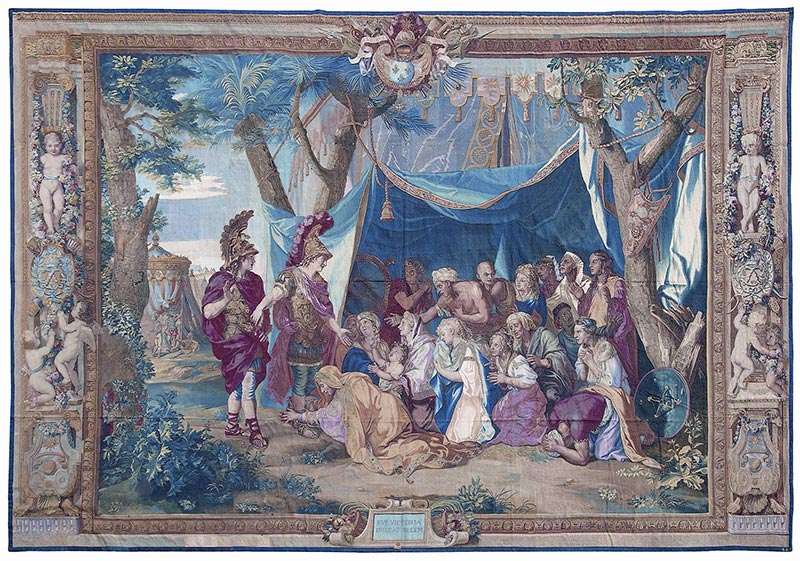

The Queen’s of Persia at the Feet of Alexander the Great (before 1670), Jean Jans père after Charles Le Brun. Mobilier national, Paris

The Problem with Colour: Charles Le Brun between Academy and Gobelins (Wolf Burchard)

Colour always was a problem. Although the initial success of the Gobelins in the reign of Henry IV had been based in large part on the vibrancy and durability of their in-house-produced dyes, and less on the complexity of the tapestries’ designs, dyers were still considered to be of a much lower rank than weavers. Their status was at least as low as that of colour grinders at the Academy – if not inferior. Their hard work was considered to have no artistic or intellectual component. It was very dirty and very smelly.

Acquisitions of the Month: June 2015

Vallayer-Coster was just 26 when she was elected to the French Academy. She was famous for her flower paintings and still lifes, two of which – Still Life with Brioche, Fruit and Vegetables (1775) and Floral Still Life (an undated miniature) – are already in the collection. But as this exquisite portrait shows, she also turned her hand successfully to other genres.

Pablo Bronstein on Chatsworth, the Grand Tour and his love of delft

They’ve got unbelievable Old Master drawings at Chatsworth, but very often on subjects that I didn’t think were particularly relevant – I wasn’t that interested in showing endless Raphaels of impeccably drawn calf muscles. What they have is very good delft and silver, which by chance is totally up my street.

Palace (1943), Joseph Cornell. © The Joseph and Robert Cornell Memorial Foundation/VAGA, NY/DACS, London 2015. Photo: The Menil Collection, Houston. Photography: Hickey-Robertson

Wanderlust: Joseph Cornell finally arrives in Europe (Jasper Sharp)

It never really seemed probable that Joseph Cornell (1903–72) would become an artist. He could not draw, paint or sculpt. He received no formal artistic education, worked a string of blue-collar jobs to support his mother and disabled brother, and rarely travelled far beyond the family home on Utopia Parkway in Flushing, New York. And yet, tucked away in its cramped basement, he assembled one of the most remarkable and original bodies of work of any artist in the 20th century.

A coastal landscape with fisherfolk, a beached boat beyond (c. 1826), Richard Parkes Bonington. Christie’s London (estimate: £2m–£3m)

Market Preview: July/August 2015 (Susan Moore)

One of the most exceptional – but far from most expensive – paintings on offer this season at Christie’s London is a coastal landscape by Richard Parkes Bonington. This is another market rarity, too, partly because of the brevity of the artist’s career – he died from consumption at the tender age of 26 – but also because he turned to painting in oils just five years or so before his death.