From the September 2023 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

What is the point of a museum? This question is increasingly more fraught as competing interests battle for what they see as the soul of the institution. For some, not being represented exactly as they wish to be represented by a museum lessens that museum’s claim to be part of the public sphere. As institutions try to offer something to everyone – entertainment, child care, education – it can seem to many as if they fail to provide anything at all. But if we allow experts to do what they are expert in, then what would museums themselves like to do?

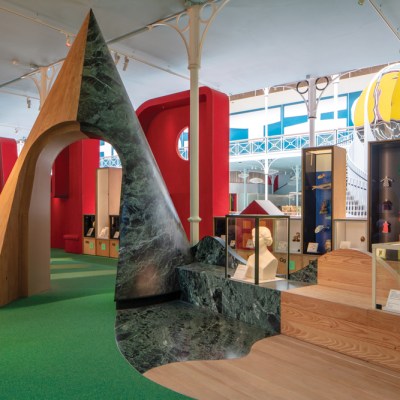

Two events of the summer prompted these questions. The first was the reopening of the V&A’s Museum of Childhood in east London under the new name of Young V&A. The second was the appointment of Will Gompertz, previously artistic director of the Barbican Centre, as the new director of Sir John Soane’s Museum.

Second thing first. When a museum selects a new director the appointment usually indicates what the institution’s priorities are – or are going to be – and what broader operational skills it feels it is lacking. The role of museum director demands certain qualities: being good with donors, knowing how to run an organisation and having a sense of how to unite unwieldy organisations around a single narrative. Gompertz began his career in the press and media department of the Tate. He then became the BBC’s arts editor before taking up his post at the Barbican. He is often described as a great communicator. His arrival at the home of one of the UK’s most important (and learned) architects suggests that the trustees are anxious about how well the museum is communicating its mission and alerting everyone to the riches of the collection. But is more PR what’s really needed in these media-saturated times?

Young V&A suggests another line of thought. As Isabel Stevens points out, museums designed for children are changing – and so is the attitude of most other museums towards children. But there is another factor at work. At Young V&A there is an unassailable belief that its collection is there to encourage its audience to think of itself as an audience. The wall texts and the signs all work hard to include the viewer in the exhibition. When I visited in August, I came across a sign in a display dedicated to colour that asked: ‘What is your happy colour?’ I may not be the intended audience for the sign – and it may seem curmudgeonly to point it out – but this is a museum that prioritises happiness and a sense of self. Young V&A seems intent on training its younger visitors to become museum-goers. If you can get them excited by disco lights in a doll’s house at the age of five, surely they will make a beeline for an exhibition of incunabula at ‘Old V&A’ at the age of 25?

As you walk out of Young V&A the first thing you see, on the other side of the road, is a car wash. Above the whirring brushes is a sign that says ‘Soft Wash’. The exercising of soft power is, of course, something in which international museums are adept. ‘Washing’ the histories of their collections is also something museums do on a regular basis. How gently do you have to wash something to make it attractive, how much soft soap is required – and what about all those difficult truths lurking in the archives?

From the September 2023 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.