All objects may be regarded as cultural or historical documents – ask an archaeologist – but some are more resonant than others. This particular work of art – and a presentation sword is very definitely that – commemorates an episode of such unbelievable swashbuckling bravado that it is hard to believe that Errol Flynn was never asked to take the hero’s role in a 1930s Hollywood biopic.

The action takes place during the Napoleonic Wars but this is a tale as much about trade – and booty – as politics. On 31 January, 1804, a convoy of 16 East India Company merchant ships and a number of smaller vessels under the command of Commodore Nathaniel Dance set sail from Canton to Europe with a cargo of tea, silk and porcelain valued at around £8m – the equivalent of over £600m today. When it reached the narrow Strait of Malacca – still a pirate’s paradise – four sails were spotted on the horizon. They turned out to belong to a French squadron commanded by Admiral Linois comprising the 74-gun Marengo and three frigates.

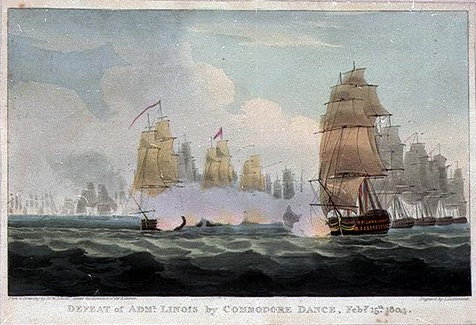

Defeat of Admiral Linois by Commodore Dance, February 15th 1804 (1804), William Daniell. National Maritime Museum

Dance had two choices. He could turn and run, but he knew that his ships would easily be captured. The alternative was to face the French, raise ensigns as if for battle, and hope his merchantmen were mistaken for British men-of-war. He did, they were, and after a brief exchange of fire the French withdrew. If the French had seized the cargo, both the Honourable East India Company and Lloyd’s of London would probably have been ruined.

Dance had most probably been inspired by an incident off the coast of Brazil some four years earlier when East Indiamen were similarly beset by French warships. Here the hero of the hour was Captain Henry Meriton of the Exeter who, finding himself at midnight alone and coming up fast to the Médéé, with great presence of mind ran alongside with all his gunports up and commanded that the French captain surrender to superior forces. He did. On the awful realisation that he had surrendered to a merchant ship (his was the only warship ever to have struck its colours to a merchantman), he begged to be allowed ‘to fight the battle again’. Among this fleet of East Indiamen was also the Coutts, commanded by Captain Robert Torin, and both he and Meriton later took part in Dance’s Action. It was for this that Torin (like each of his fellow captains) was awarded a sword of £50 value from the Patriotic Fund of Lloyd’s of London.

Dance had most probably been inspired by an incident off the coast of Brazil some four years earlier when East Indiamen were similarly beset by French warships. Here the hero of the hour was Captain Henry Meriton of the Exeter who, finding himself at midnight alone and coming up fast to the Médéé, with great presence of mind ran alongside with all his gunports up and commanded that the French captain surrender to superior forces. He did. On the awful realisation that he had surrendered to a merchant ship (his was the only warship ever to have struck its colours to a merchantman), he begged to be allowed ‘to fight the battle again’. Among this fleet of East Indiamen was also the Coutts, commanded by Captain Robert Torin, and both he and Meriton later took part in Dance’s Action. It was for this that Torin (like each of his fellow captains) was awarded a sword of £50 value from the Patriotic Fund of Lloyd’s of London.

This fund had been formerly inaugurated at a meeting at Lloyd’s Coffee House in 1803, but the insurance underwriters who gathered there for business had long raised money for those wounded among the fleet and for the dependents of those killed. Now, buoyed by public contributions at the outset of the war, it was decided also to reward those who distinguished themselves with ‘successful exertions of value or merit’. Rewards took the form of a silver vase, a sword or a sum of money. The swords, made by sword cutler Richard Teed in the Strand, were awarded according to rank, and worth £100, £50 or £30. Such presentations officially ceased in 1809, and this was the only occasion when swords were presented to officers of the Merchant Navy.

Captain Torin was presented with a Lloyd’s Patriotic Fund sword for his part in ‘The Battle of Pulo Aura’ in 1804. Photo: Peter Finer

Captain Torin’s handsome sword is now making its way to Maastricht and the stand of arms and armour specialists Peter Finer at TEFAF (10–19 March). Given the nature of the commission and the taste of the age, it is hardly surprising to find it replete with heroic classical allusions. The knuckle-guard of the stirrup hilt takes the form of a club of Hercules entwined by a snake, the quillons are Romanic fasces and the langets are cast with acanthus foliage and applied with naval trophies. The pelt of the Nemean lion ornaments the back piece of the ivory grip, and various Labours of Hercules adorn the gilt-bronze mounts of the scabbard. The curved blade, profusely etched and gilt against a bright blued ground, also features patriotic figures of Britannia and Hope, a conch shell and mermen.

Given the financial disaster averted by the pluck of Dance and his officers and seamen, it is pleasing to report that all were widely rewarded. As for the swords, they fared less well. According to Roley Finer, a £50 sword in 1950 would have cost around, well, £50. These days expect to pay ‘a six-figure sum’.