From the November 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

‘The artist thinks slowly,’ says a jaded-looking William Kentridge in Drawing Lesson 17 (A Lesson in Lethargy) (2010). We are spying on him in his studio as he scribbles in a notebook – accompanied as we do so by a second Kentridge, identically dressed in crisp white shirt and spectacle retainers, who peers over his double’s shoulder, casting scorn. ‘He hopes that if he keeps writing slowly,’ Kentridge says of Kentridge, ‘slowly some idea will germinate in his brain and come towards the front. But in case it doesn’t, he writes very badly so that not even he can read what he’s written down. I mean, what do any of these things say?’

Finding this film midway through the exhibition of Kentridge’s work currently at the Royal Academy of Arts in London – the South African’s largest survey in the UK to date – you would be forgiven for thinking of it as merely put-on self-deprecation. Surely an artist as prolific as Kentridge, who has taken on mediums ranging from drawing to animation, film, tapestry, sculpture and opera, has no time for self-doubt, let alone slow thought? And yet, seen in another light, slowness and indecision might be the keys to Kentridge’s peculiar power.

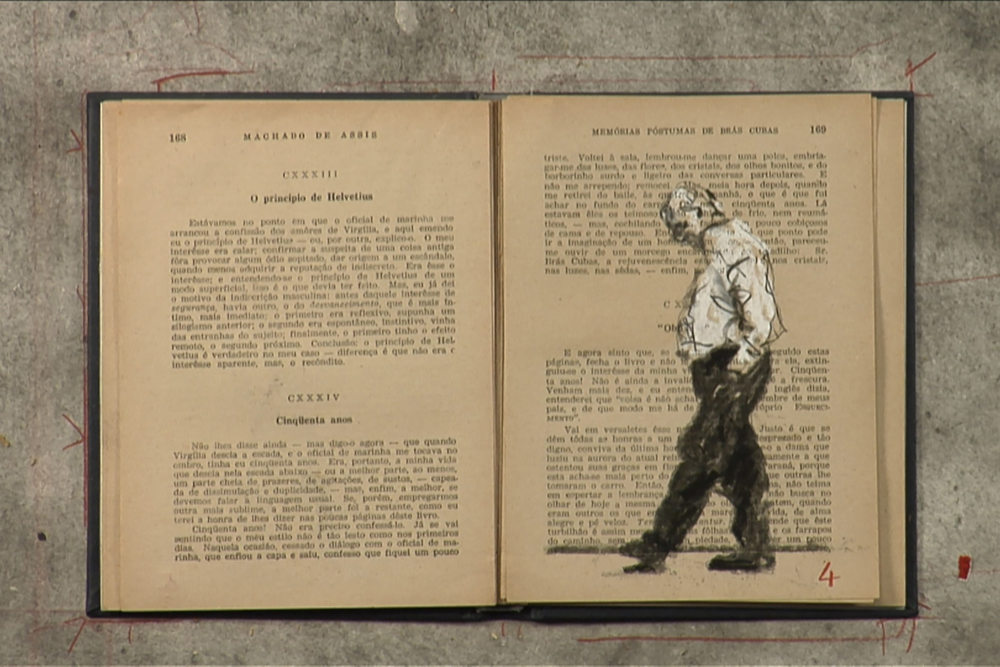

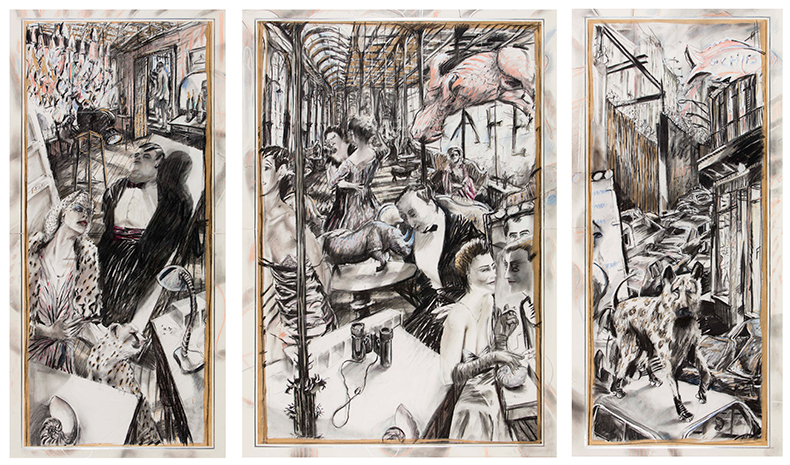

The Conservationists’ Ball (1985), William Kentridge. Rupert Museum, Stellenbosch Courtesy the artist; © William Kentridge

He was, by his own admission, a slow starter. The son of two prominent anti-apartheid lawyers – his father defended Nelson Mandela and represented the family of Steve Biko – Kentridge spent his twenties in odd jobs; he thought he might be a jeweller, then an actor (his understanding of the theatre has remained fundamental to his work). But it was only when he was pushing 30 that he committed himself to drawing, realising belatedly that, ‘If you’re going to succeed in something, you have to specialise and focus on it.’ The measure of his success is made clear in the first room of this exhibition: by the mid 1980s, charcoals such as The Conservationist’s Ball or Koevoet (Dreams of Europe), both from 1985, have all the satirical snarl in their depictions of middle-class Johannesburg of George Grosz or Otto Dix’s castigations of Weimar Germany. Blank-faced, besuited men and finely robed women cavort in bars and ballrooms. Alongside them are cheetahs, hyenas and rhinos – intrusions of the African wilderness they have tried so hard to shut out.

In 1989, Kentridge became one of those rare artists who manage to create an entirely new form to suit their needs. Stop-motion animation usually presents successive drawings, one to a frame – but with the first of his Drawings for Projection, Kentridge began to tweak and rub at the same underlying drawing, before returning to his camera and shooting the next frame, such that the final animation bears the mark of previous scenes that have not been entirely erased. The effect is deeply intimate – you watch the mind at work, and the mind here does indeed work slowly; a nine-minute film can take a year to complete, and Kentridge has pointed to the irony that to achieve the illusion of slow movement, he actually has to draw faster, to produce more frames per second. But it is also resonant with Kentridge’s broader, complex political outlook; the inherent messiness of these films is a formal repudiation of the glib notions of ‘truth’ and purity exerted by authoritarian regimes in their attempts to control history. Nothing ever truly disappears, these films insist; the past always leaves a stain.

Drawing for Other Faces (2011), William Kentridge. Courtesy the artist; © William Kentridge

Drawings for Projection revolve around the recurring characters of Soho Eckstein, a cigar-smoking mining magnate, and the impoverished young artist Felix Teitelbaum, whose resemblance to Kentridge himself is clear – though their interactions never quite resolve into plot. At the RA, five of the 11 are presented in the same room – including the first, Johannesburg (1989), 2nd Greatest City After Paris, and the most recent, City Deep (2020). Each is accompanied by a megaphone, the soundtracks of the individual films merging together as you watch. It is hard not to be distracted by what is going on over your shoulder, disrupting and complicating any sense of linear progression. The excoriating vision of apartheid South Africa in the first film, which sees Soho buying up half of Johannesburg while Teitelbaum fantasises about an affair with Eckstein’s wife, gives way to more ruminative visions – in the last, Johannesburg Art Gallery crumbles around Eckstein’s ears. Transitions become more elaborate; the music develops from crackling jazz scores reminiscent of silent films to elaborate choral compositions invoking ancestral spirits. Ideas take shape before your eyes in these films – and yet that shape is never fixed, never final. An ampersand that morphs into gallows in one film reappears elsewhere, only to become a dancing grim reaper.

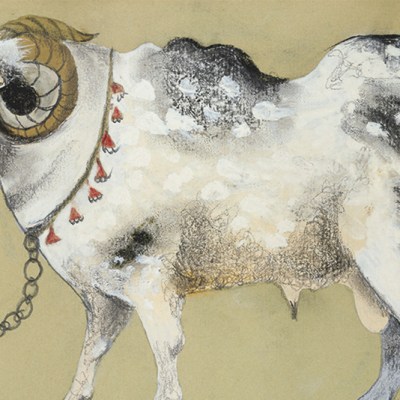

Notes Toward a Model Opera (film still; 2015), William Kentridge. Courtesy the artist; © William Kentridge

The exhibition progresses from Drawings for Projection to a sequence of huge tapestries based on colonial-era maps, Kentridge’s take on Alfred Jarry’s Ubu Roi (here a corpulent low-ranking civic officer, watched by an eye on a stalk), other films including Black Box/Chambre Noire (2005) – which incorporates a miniature stage maquette, devised while Kentridge was working on a production of The Magic Flute, in a retelling of the German genocide in Namibia – and Notes Towards a Model Opera (2015) a riff on the state-sanctioned operas of Maoist China.

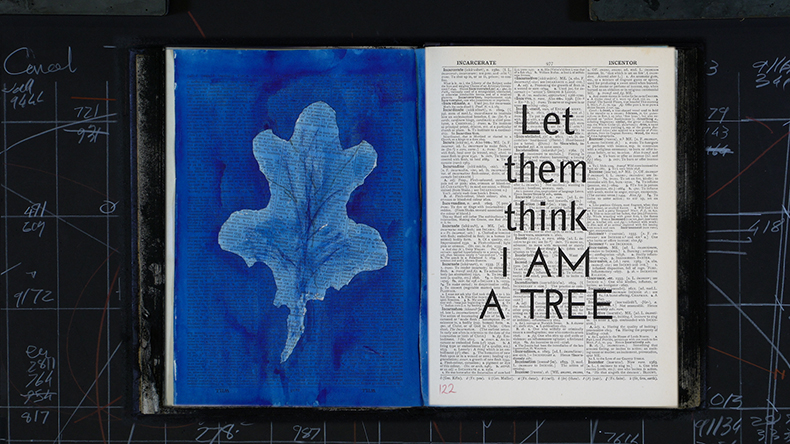

There is ample indication of Kentridge’s extraordinary range of reference here – from Mozart to Mao to Manet to Gerard Manley Hopkins – but the show is not a retrospective, as such; key works such as More Sweetly Play the Dance (2015) are not to be found here. But then aiming for completeness has never been Kentridge’s style. The final, most recent work – Sibyl (2020) – is among his best. Based on the opera Waiting for the Sibyl, which premiered in Rome in 2019, it adapts Virgil’s telling of the tale of those who sought out the Sibyl at the gates of Hades to learn their fate. In Kentridge’s hands, it becomes a tale of the power exerted by bureaucracy; cryptic instructions – ‘Start dying, assiduously, wisely, optimistically’ – flicker on the pages of reference books, accompanied by soaring choral music.

Waiting for the Sibyl (film still; 2020), William Kentridge. Courtesy the artist; © William Kentridge

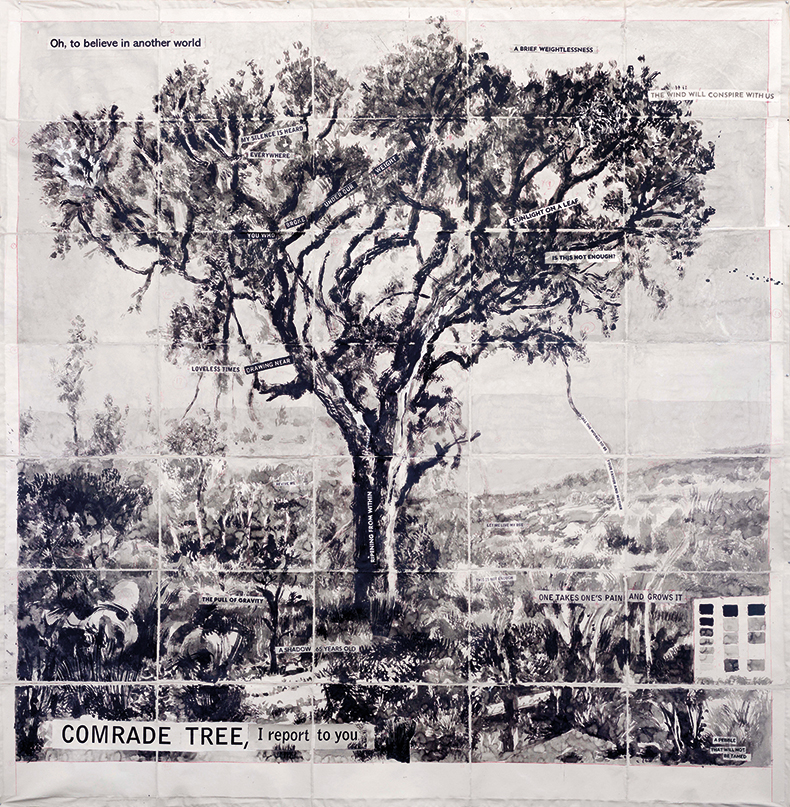

In the room outside hangs a series of Kentridge’s large-scale charcoal collages of trees, each adorned with the maxims Kentridge plucks out, magpie-like, from his reading. ‘The past is too tight,’ one tells us – and this is a sentiment that pervades all of Kentridge’s work. Sometimes, as in the rare beauty of Sibyl, he gives us a chance to briefly wriggle free, with moments of clarity and optimism. But even then, there’s the need to keep one eye looking back over your shoulder.

Comrade Tree, I Report to You (2022), William Kentridge. Courtesy the artist; © William Kentridge

‘William Kentridge’ is at the Royal Academy of Arts, London, until 11 December.

From the November 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.