This first UK survey of the Finnish painter traces her career from realist works shown at the Paris Salon in the 1880s to her later modernist style. With a room devoted to the proving self-portraits Schjerfbeck painted throughout her life, the show also considers her fascination with the process of ageing. Find out more from the Royal Academy’s website.

Preview the exhibition below | View Apollo’s Art Diary here

Self-portrait (1884–85), Helene Schjerfbeck. Photo: Hannu Aaltonen/Finnish National Gallery

Born in Helsinki in 1862, Schjerfbeck began studying at the Finnish Drawing School at the age of 11. At 18, she travelled to Paris to continue her training. Her early paintings, like this self-portrait, were heavily influenced by the naturalism of French painters such as Jules Bastien-Lepage.

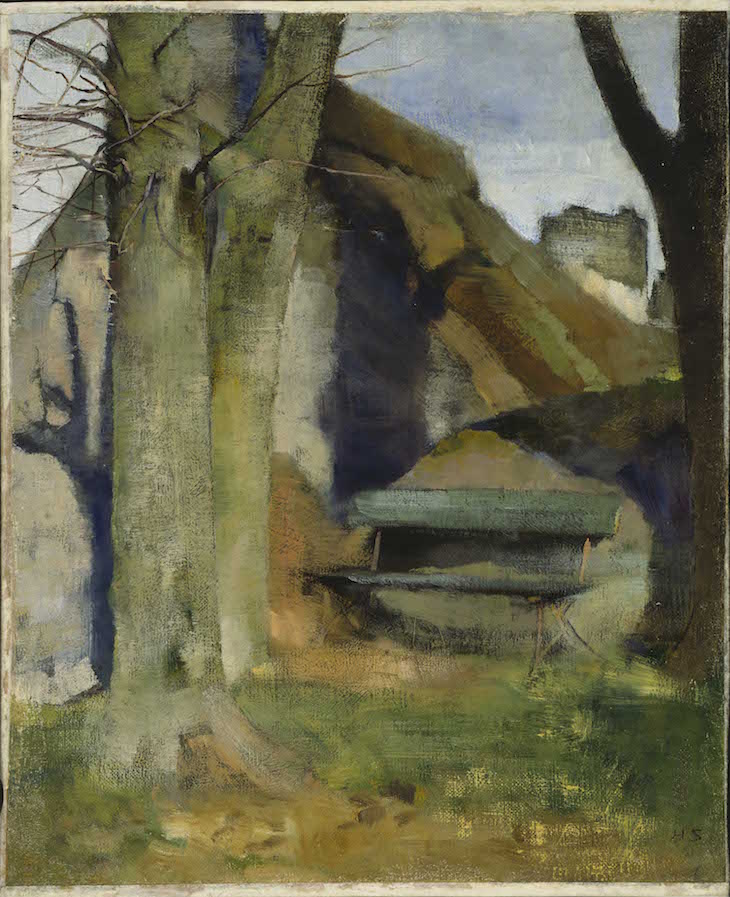

Shadow on the Wall (1883), Helene Schjerfbeck. Photo: Hannu Aaltonen/Finnish National Gallery

Schjerfbeck spent much of the 1880s travelling between Paris, Finland, and Pont-Aven in Brittany – she also had an extended stint at the artists’ colony in St Ives, where she stayed with the painters Marianne Preindlsberger and Adrian Stokes. In this Breton landscape, light, scumbled brushstrokes allow the material of the canvas to show through – an early example of her experimentation with non-realist approaches.

My Mother (1909), Helene Schjerfbeck. Photo: Yehia Eweis/Finnish National Gallery

In 1902, Schjerfbeck moved to the rural town of Hyvinkää, 30 miles north of Helsinki, to look after her ageing mother, with whom she had a cold and difficult relationship. This spare, melancholy portrait of Olga Johanna Schjerfbeck, in which the canvas is divided into separate fields of neat colour, demonstrates the evolution of the artist’s increasingly modernist style. It makes a clear nod to Whistler, whom Schjerfbeck admired.

The Family Heirloom (1915–16), Helene Schjerfbeck. Photo: Yehia Eweis/Finnish National Gallery

This picture shows Schjerfbeck’s brother holding up a red box, over which are bent the heads of Schjerfbeck’s neighbours, Jenny and Impi Tamland, who helped the artist look after her household. The vivid red of the box, echoed in the girls’ lipstick, shows Schjerfbeck’s growing mastery as a colourist, influenced by the bold hues used by French Modernism.

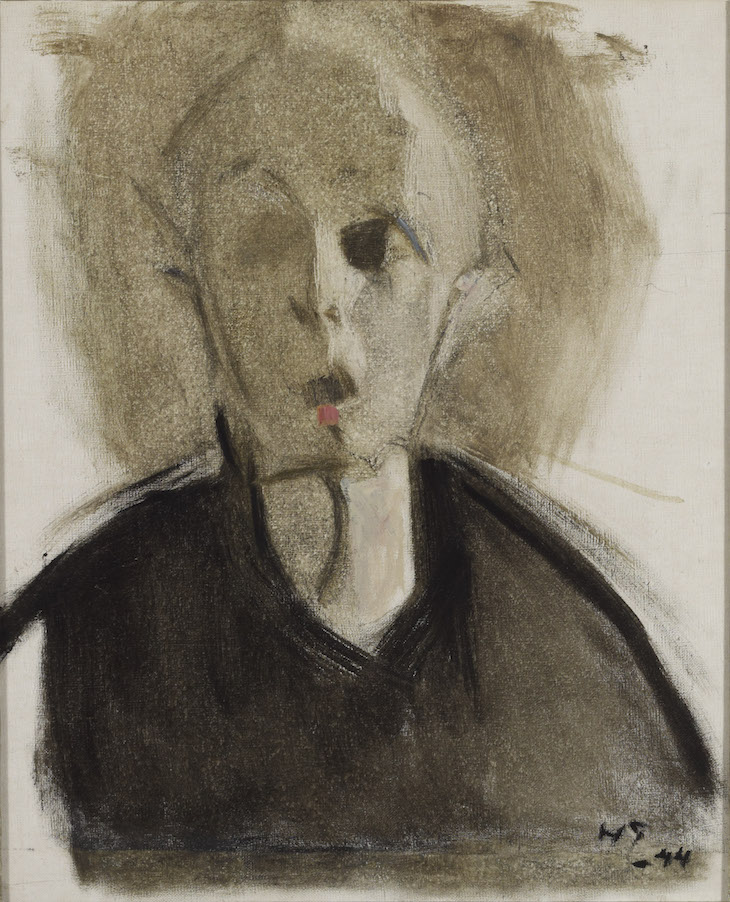

Self-portrait with Red Spot (1944), Helene Schjerfbeck. Photo: Hannu Aaltonen/Finnish National Gallery

In her final years, which Schjerfbeck spent in Sweden after being evacuated due to the war, she produced a number of radically simplified still lifes, verging on abstraction, and a series of more than 20 haunting self-portraits: confrontations with isolation, ageing, and the approach of death. Schjerfbeck has often been called ‘Finland’s Munch’, reflecting the sense of melancholy that pervades the artist’s late work.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](https://apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Sitting pretty: the world’s best museum benches